Gemstone (1972)

“I just met the most amazing man. He showed me how you could kill someone with a pencil,” gushed Lydia Odle, the wife of a Nixon loyalist. She explained how the fatal method involved holding the eraser end of the pencil in one’s palm and jamming the other end of the pencil (preferably freshly sharpened) in someone’s neck, above the Adam’s apple. Such was the reputation that G. Gordon Liddy liked to create for himself. His boss, Jeb Magruder, deputy director at the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CRP) called him “a cocky little bantam rooster who liked to brag about his James Bond-ish exploits.” Liddy, a former FBI agent, was working as legal counsel for the Committee in 1972, but what he really wanted was to work in espionage. In a dream that would have been more at home in the CIA, he aspired to commit blackmail, kidnapping, and murder and would use his position at the CRP to make his fantasies a reality.

With his focus distracted with covert operations on his mind and his boss Magruder being far too young and lacking experience, in his view, to assign him work, this situation came to a head when Magruder approached Liddy one Friday in the CRP reception area:

“Gordon, where are those reports you promised me?”

“They’re not ready,” Liddy retorted angrily.

“Well, the delay is causing me problems,” Magruder informed him. “If you’re going to be our general counsel, you’ve got to do your work.”

Magruder then made the mistake of putting his hand on Liddy’s shoulder.

“Get your hand off me,” Liddy screamed. “Get your hand off me or I’ll kill you!”

When he was not threatening to murder his superior, he worked on putting together an intelligence plan for the Democratic National Convention, planned to be held in Miami in July 1972. Magruder had not even bothered to look into what Liddy was planning for the event, and in retrospect, he wish he had. The meeting took place on January 27, 1972 in the office of John Mitchell, who had not yet resigned as Attorney General to run Nixon’s reelection campaign. “Liddy laid out a million dollar plan that was the most incredible thing I have ever laid my eyes on,” Mitchell recalled.

White House counsel John Dean similarly marveled at how Liddy had managed to put together such a presentation, with professionally prepared charts, in such short order; he thought that Liddy had been buried in legal work, which was after all his day job. With self-assured confidence, Liddy led them through a presentation covering an operation he called Gemstone, a plan to disrupt the Democratic National Convention with “mugging squads, kidnapping, sabotage, the use of prostitutes for political blackmail, break-ins to obtain and photograph documents, and various forms of electronic surveillance and wiretapping,” according to Magruder and confirmed by the others in attendance.

Magruder recalled that Liddy “wanted to employ call girls, both in Washington and Miami Beach during the Democratic Convention, who would be used to compromise leading Democrats. He proposed renting a yacht in Miami Beach that would be set up with hidden cameras and recording devices. The women would lure unsuspecting Democrats there for what would be, unbeknownst to them, a candid camera session.”

“These would be high-class girls,” Liddy assured the men. “Only the best.”

Dean interrupted Liddy’s presentation: “How in the world is some whore going to compromise these guys at the convention? They’re not that dumb.”

Gordon shot him an irritated look: “John, these are the finest call girls in the country. I can tell you from firsthand experience—" The attendees all broke into laughter, which relieved the tension. “They are not dumb broads,” Liddy continued, “but girls who can be trained and programmed. I have spoken with the madam in Baltimore, and we have been assured their services at the convention.”

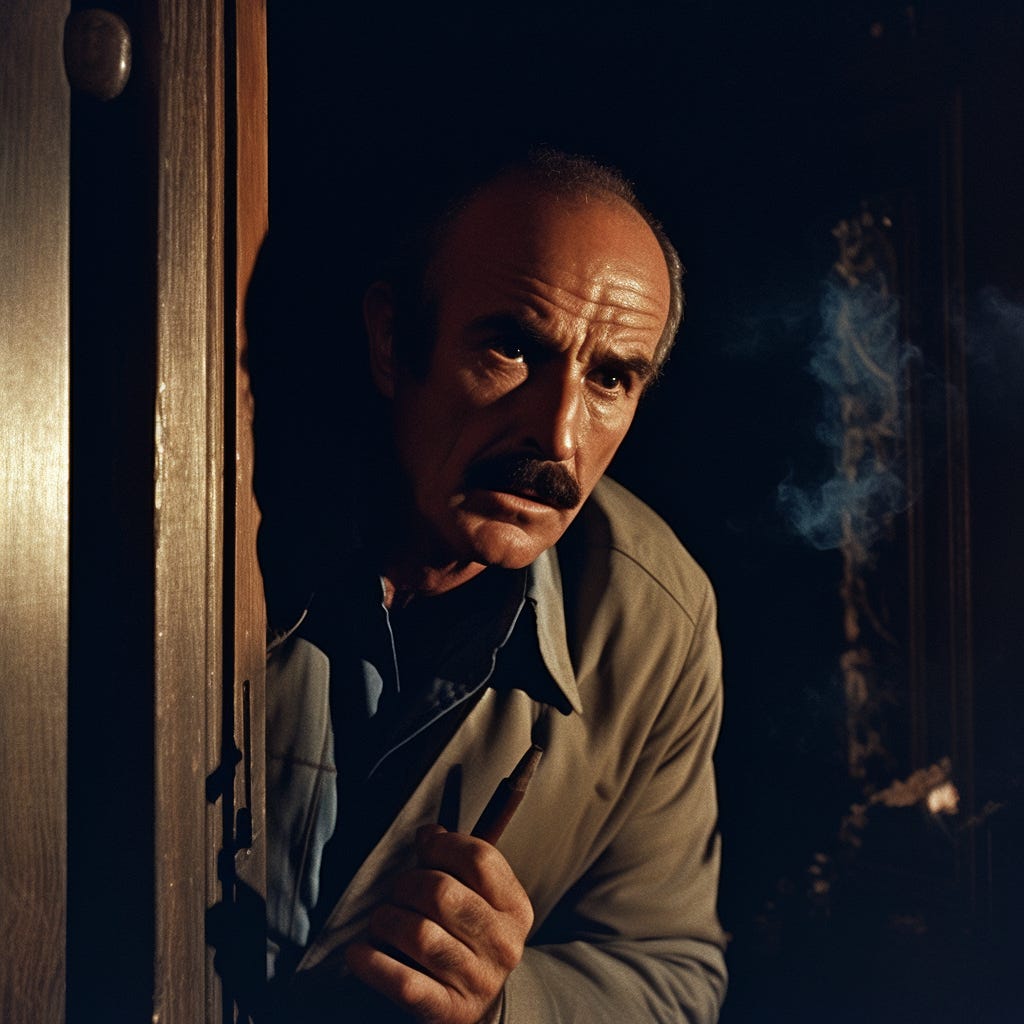

At the end of the presentation, the attendees sat in silence for a minute, Mitchell puffing on his pipe, eventually offering: “Gordon, that’s not quite what we had in mind, and the money you’re asking for is way out of line. Why don’t you tone it down a little, then we’ll talk about it again?”

Liddy was stunned by the lack of support for his initiative; “I thought that was what he wanted,” he lamented in the moments afterwards. In perhaps an act of revenge against his former boss whom he despised, Liddy later recounted Magruder and having designs on the prostitutes in a later iteration of the Gemstone plan:

“Magruder approved the drastically revised plan, even to the point of agreeing to my demand that moneys spent to date not be charged against the new $250,000 budget. He had only one suggested change: that the prostitutes to be used at the Democratic convention next summer be brought up to Washington from Miami and put to work immediately.

“I told Jeb that bringing whores to Washington was like shipping cars to Detroit, with all the free stuff being given away on Capitol Hill they’d just be a couple of more grains of sand on the beach. Besides, the budget was bare bones; there wasn’t a nickel left over for their transportation and payment for all those months until summer….

“Magruder didn’t want to let the subject go. If he could justify a trip to Miami, could I fix him up with our girls? Jesus, I thought, the wimp can’t even laid with a hooker by himself. I saw an opportunity to turn Magruder’s lust to advantage. If GEMSTONE were approved, I told him, he’d be paying for them anyway and could take his pick. From the look on his face as I left his office, I had the feeling that if Magruder had anything to say about it, GEMSTONE would be approved.

Magruder had concluded Liddy was a “weird guy”; he once asked Liddy why he had bandages on his hand, after trying to ignore Liddy’s injury for a week: “I was meeting with some important contacts,” Liddy explained in a conspiratorial whisper. “I had to show them I could take it. So I held my hand to a blowtorch. That’s what you call mind over matter—mental discipline.” Dean heard a variation on the story that became repeated White House lore: “I held my hand over a candle until the flesh burned, which I did without flinching. I wanted them to know that I could stand any amount of physical pain.” Dean began to suspect that Liddy, whom he termed “a strange bird,” had been pawned off on them from other White House staff. “Bud [Krogh] might have touted Liddy to me to unload him from his own staff,” he pondered. “It’s an old trick, sell the bad apple elsewhere; I had done it myself. But this could be serious.”

Gunn & Castro (1960-1963)

In 1960, pressure was mounting from the White House to assassinate Fidel Castro. When the CIA was not plotting how to accomplish this goal, it was subsidizing local businesses. Robert Maheu, a former FBI special agent turned private investigator, had an office in Washington and to help him survive his first few months on his own, the CIA offered assistance. His former FBI colleague Robert Cunningham, now with the CIA Office of Security, despite an obvious conflict of interest gave Maheu $500 a month (worth around $5,500 today) to bolster his finances. The CIA later called to collect on their investment: they needed access to the Mafia underworld and thought Maheu would have such contacts. After some pressure, Maheu reluctantly agreed to make contact with Johnny Roselli, who lived at the time in Los Angeles, ostensibly earned a living from ice-making machines on the Las Vegas Strip and was thought to be a member of the Mafia. The plan was for Maheu to approach Roselli, pretending to represent Cuban business interests, with an authorization from the CIA to offer $150,000 ($1.5 million today) in exchange for eliminating Castro.

Dr. Edward Gunn, Chief of the CIA’s Office of Medical Services, received a box of lethal cigars, thought to be Castro’s favorite brand, on August 16, 1960. Fifty cigars in total were poisoned with botulinum toxin to such an extent that they were expected to cause death within a matter of hours for anyone who merely put one in their mouth. Gunn took the cigars into his possession and placed them in his safe, awaiting delivery.

During the week of September 25, 1960, CIA case officer James P. O’Connell (another former FBI special agent) met with Maheu and Roselli in Miami, where Roselli introduced them to “Sam Gold,” who in reality was Sam Giancana, a mobster and head of the Chicago Outfit, who in turn would use “Joe” (actually Santos Trafficante, the head of the Cosa Nostra in Cuba) to take out Castro. They discussed the means for the assassination, the Agency suggesting a gangland-style killing where Castro would be shot publicly. Giancana immediately responded that this would not work, given that the chance of surviving such an event would be nil and thus make it difficult to recruit for the effort. Giancana preferred the idea of adding a lethal substance to Castro’s food or drink and mentioned that Trafficante had access to an individual in Castro’s circle who could accomplish this task: Juan Orta, Chief of Castro’s Office, who had grown accustomed to gambling kickbacks that had since dried up and could be enticed to do the job for money.

The CIA officers tried developing poison pills to realize this method, but when tested, the pills failed to disintegrate at all in water. After creating a batch that was more soluble, the pills were given to Dr. Gunn along with funds to purchase guinea pigs to test the substance’s lethality. The guinea pigs survived, with Ray Treichler of the CIA’s Technical Services Division identifying the source of the problem: the animals had a high resistance to botulin. Gunn tried again, recalling that for “a subsequent batch, one out of four guinea pigs did depart.” Treichler tested the pills on monkeys as well and found they had the desired effect. Gunn attended a meeting in which a pencil was revealed as the concealment device to deliver the deadly pills. In early 1961, O’Connell received six pills, handing three to Roselli. These pills then made their way through Trafficante and finally to Orta in Cuba while the Agency awaited the results. Orta returned the pills a few weeks later: he was not up to the task and got cold feet, the gangsters reported. In reality, Orta had already lost his position in Castro’s Office by the time the poison arrived. The Agency tried another candidate to deliver the pills, again with no results.

In March 1961, Roselli pointed the Agency to another prospect who could carry out the killing: Tony Varona, head of the Democratic Revolutionary Front, a group that happened to be funded by the CIA. The Agency was aware that Varona was dissatisfied with the amount of support he was receiving and the CIA in turn suspected he was not keeping his end of the bargain. The CIA received information from the FBI that Varona was part of a plan to implement anti-Castro activities to secure gambling, prostitution and drug business in Cuba if Castro were to be overthrown. Their desires seen as mutually beneficial, Trafficante approached Varona with an offer to pay $50,000 ($500,000 today) for the job, which was enthusiastically accepted. Roselli gave additional pills to Varona, whose plan was to place them in Castro’s drink while visiting one of his favorite restaurants in Cuba. The Agency believed this plan failed because Castro had ceased visiting that particular establishment. By this point, Roselli was certain he was dealing with “a government man—CIA” but he assured them as a loyal American, he would help as best he could without payment and never reveal the operation.

The Castro operation went quiet after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of April 1961 until a year later, when Varona was handed additional poison pills and the Miami CIA Station known as JMWAVE additionally bought for him “explosives, detonators, twenty .30 caliber rifles, twenty .45 caliber hand guns, two radios, and one boat radar,” according to a later report. The Station Chief Ted Shackley sat in a parking lot of a drive-in restaurant while he and Roselli separately watched as a U-Haul holding the arms and equipment was driven away, later returned empty with the keys under the seat.

Robert F. Kennedy, then Attorney General of the United States, learned of the Castro operation in May 1962 after Maheu had been caught wiretapping a hotel room in Las Vegas as a favor returned to Giancana who had assisted in the Castro assassination plot. Rather than potentially expose the Castro plot, Kennedy agreed that prosecuting Maheu did not make sense and that “I trust that if you ever try to do business with organized crime again—with gangsters—you will let the Attorney General know before you do it.”

Several other plots against Castro were prepared throughout 1963, including a poisoned diving suit and a booby-trapped sea shell meant to exploit Castro’s fondness for scuba diving. The efforts culminated in a meeting in Paris with Rolando Cubela, a member of the Cuban revolutionary effort turned CIA asset. Cubela had requested a high-powered rifle with a silencer to do the job, but also expressed a preference for a more surreptitious method of assassination so as not to blatantly risk his own life. Dr. Gunn spent an entire night preparing for him upwards of eight prototypes of a hypodermic syringe disguised as a ballpoint pen to deliver Black Leaf 40, a poisonous insecticide. Gunn was proud of his efforts: the Paper-Mate pen’s needle was so fine the victim would hardly notice it, comparing it to a “scratch from a shirt with too much starch.” A CIA officer, Nestor Sanchez, greeted Cubela in the late afternoon of November 22, 1963 and showed him the poison pen device, explaining how it worked. Cubela was not particularly impressed; as a doctor, he said, he knew all about Black Leaf 40 and that “surely [the CIA] could come up with something more sophisticated than that.” At the same time they were meeting to discuss Castro’s assassination, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. The two learned the news as they left their meeting. Cubela, visibly upset, wondered aloud: “Why do such things happen to good people?”

In a 1967 CIA report, the Inspector General noted that all of the plotting to assassinate one person may not have even led to the final outcome of toppling the regime. An early Agency research paper “took the position that the demise of Fidel Castro, from whatever cause, would offer little opportunity for the liberation of Cuba from Communist and Soviet Bloc control.” As part of the Inspector General investigation, Treichler tested a cigar he had kept from the contaminated batch all of these years later; it had maintained 94% of its deadly effectiveness. None of this information on assassination plots was brought forward to the Warren Commission, despite Allen Dulles having been briefed on the Castro operation and sitting on the Commission itself. Dr. Gunn deceptively later told investigators when asked if there had been other targets besides Castro: “I have no offensive plans I know of. My work called for saving and preventing friends from having trouble, but no offensive plans.”

Aspirin Roulette (1972)

Gunn retired from the CIA in 1971, but upon meeting him, Liddy believed that this assassination expert had to still be in the Agency’s employ. With Liddy’s Gemstone operation stalled, on March 24, 1972, Liddy and E. Howard Hunt met with Gunn to learn from this physician the most effective manner to kill the journalist Jack Anderson. “I was asked if I could help them,” Gunn later testified, “by providing a behavior-altering drug which they indicated would be given to an individual who was never identified.” The trio met for lunch in a basement restaurant at the Hay-Adams Hotel near the White House.

A former CIA officer himself, Hunt had been busy recruiting Cuban exiles he knew from his days involved in the Bay of Pigs operation assist with covert operations for the White House. He had also assisted Liddy with breaking into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist to try to uncover dirt to discredit him after his unauthorized disclosure of the Pentagon Papers. Since Gunn had tried to eliminate Castro through the use of drugs, he was a natural contact to be offered by the Agency. Gunn’s “retirement” had to be a cover—a standard technique, Liddy thought.

Jack Anderson earned his place on Richard Nixon’s enemies list through his publishing of official secrets and embarrassing stories in newspapers dating back to 1960, when Anderson revealed Nixon’s brother Donald had received a $205,000 loan from Howard Hughes to bail out a drive-in restaurant that went bankrupt a year later, damaging Nixon’s campaign for President against Kennedy. By the early 1970s, Anderson had published a series of articles based on a cache of classified documents, as well as leaks from within the administration. One of Anderson’s assistants at the time, Brit Hume, later described the cache of documents: “At first his sources gave him only a few papers. But Jack insisted that he had to have a full set, or his stories could be challenged as being only a partial glimpse of the picture, out of context. All of the material bore the highest security classification. It was an astonishing haul.”

Of particular concern to the administration were statements such as “diplomats are saying Richard Nixon may go down in history as the President who lost Latin America,” which Alexander Haig, Nixon’s Deputy Assistant for National Security Affairs, termed as a “lack of discipline” in the State Department for revealing their dissent: “I cannot overemphasize the concern with which I view this problem area within security terms and in terms of the problems which it will pose for the President as ’72 approaches,” he wrote. It was national security information, such as revelations regarding surveillance of Soviet figures, according to Hunt, that led Charles Colson, Director of the White House Office of Public Liaison, to instruct Hunt to “stop Anderson at all costs.” Hunt and Liddy interpreted the order as requesting assassination and they turned to inventing rationales to justify their endeavor, which was at the end of the day part of a reelection campaign. Since secret information, they reasoned, could result in foreign CIA agents to be captured, tortured, or killed, surely Anderson deserved to die. Liddy recalled hearing from Hunt that “as the direct result of an Anderson story, a top U.S. intelligence source abroad had been so compromised that, if not already dead, he would be in a matter of days. That was too much. Something had to be done.” They did not bother to check the veracity of this claim. Critics years later pointed to the death of a CIA station chief in Greece as an example of how exposure of sensitive information could harm Agency personnel; however, this murder occurred in 1975, three years after Anderson’s assassination was planned, and had nothing to do with the journalist’s reporting.

That none of their information had been confirmed was of no concern to Liddy and Hunt. For his crime of annoying the powerful, Anderson was to be put to death by any number of creative means, without a trial or even a clear order to do so. The duo “spent a lot of time concocting ways to get rid of the pesky journalist,” Hunt admitted decades later. Hunt only briefly explained that one of the assassination methods involved placing LSD on Anderson’s steering wheel to cause him to crash his car.

Liddy’s account remains the only full accounting of the meeting; according to him, without telling Gunn their exact target, they discussed a range of options. First Hunt was enamored of the idea of smearing LSD on Anderson’s car steering wheel to cause him to hallucinate and ruin his reputation through erratic behavior in a public setting. As Hunt was unaware that this had been tested repeatedly decades before by the CIA, Gunn simply replied that the drug had been shown to prompt unpredictable reactions on an individual level.

“How many of our people should we let him kill before we stop him?” Liddy asked, frustrated with the proposed half-measure. Hunt, refusing to give up on LSD, suggested a massive dose to cause Anderson to lose control of the car, causing a major crash and potentially Anderson’s death. Dr. Gunn repeated his doubts on the efficacy of this method; LSD could be absorbed through the skin, he explained, but there was a possibility the target would be wearing gloves in the cold or be driven by a chauffeur. LSD was finally discarded as a viable option.

Hunt’s suggestion, however, brought to Gunn’s mind a technique that had worked overseas. “It involved catching the target’s moving automobile in a turn or sharp curve and hitting it with another car on the outside rear quarter,” Liddy recalled. “According to Dr. Gunn, if the angle of the blow and the relative speeds of the two vehicles were correct, the target vehicle would flip over, crash, and, usually, burn.” Anderson’s route involved Chevy Chase Circle, a notorious location of fatal car crashes made it an ideal candidate to carry out such an operation. Liddy was concerned this would require the services of an expert to implement, one they could not afford. Gunn was surprised at their lack of funding given the task they had been asked to implement.

The most surreptitious idea discussed at the lunch was called “Aspirin Roulette”: it would have involved breaking into Anderson’s home to replace his headache medicine with a poison lookalike in the bathroom medicine cabinet. The idea was rejected only because it carried the possibility of significant harm to others, since anyone in Anderson’s family could accidently be made the target if they were to consume the poison. Also, this method could take months to work and they did not want to wait.

The idea they eventually landed on was a simple one: make Anderson the fatal victim of street crime, for him to be another statistic of an already high crime rate in Washington, DC. With no objections raised to this method, Liddy was satisfied and on Hunt’s suggestion, he passed Dr. Gunn a $100 bill from the CRP’s intelligence funds. This would protect the ruse of Gunn being retired, Liddy thought. His non-existent “secret” was safe with them.

Soon afterwards, Hunt and Liddy discussed implementation details and they decided to put forward the Cuban exiles Hunt had already recruited as the preferred assassins. The Cubans were unaware they had been recruited as part of a political campaign, hoping in their minds that their work with Hunt would somehow lead to Castro’s ouster, almost a decade after working with Hunt on that original goal. “Hunt meant for me the resumption of the operation against Castro,” revealed Eugenio Martinez, one of the Cuban recruits who had engaged in secret CIA maritime activities against Castro starting in 1961. Hunt explained how his previous work with them led to their mistaken supposition: “They had made an assumption that by virtue of my position in the White House, by virtue of the fact that I had been a senior intelligence official that had worked intimately with them in the past…I think that they thought that somehow this was going to mean the overthrow of Castro. Some of them did.”

Hunt wondered if Colson would permit this kind of outsourcing: “Suppose my principal doesn’t think it wise to entrust so sensitive a matter to them?” he asked.

Liddy pondered this matter with stoic resolve. The non-existent agents in danger from Anderson’s articles needed him. He had to be prepared to take on any task.

“Tell him, if necessary, I’ll do it.”

Ready to Kill (1972)

At another lunch with Hunt, Liddy inquired as to the current status of plan to assassinate Anderson. Hunt told him to forget about it, implying that the plan had been rejected by Colson and Liddy asked no further questions. A short time later, Magruder invited Liddy into his office to discuss a legal matter. Liddy was beyond fed up with his boss by this point and ignored completely what he had to say. One sentence did his pique his interest, however, after Magruder complained once again about Anderson’s news articles causing embarrassment to the Nixon administration: “Boy, it’d be nice if we could get rid of that guy.” Liddy’s brain translated Magruder’s statement into a more definitive statement: “Gordon, you’re just going to have to get rid of Jack Anderson.” Liddy was suddenly interested again, but given that he despised the requester, he had no desire to propose another plot. In his view, he had already offered to kill Anderson on behalf of the White House and had been told to stand down. Now this pipsqueak wants to put out a contract on him, Liddy thought, for no more reason than that he is a general pain in the ass.

After leaving the meeting, Liddy decided to play a trick on his manager for bringing up the topic of Anderson again. In the hallway on the way to the elevator, Liddy saw Bob Reisner, Magruder’s assistant and decided to approach him. “Bob, you’ll never guess what your boss has just ordered me to do.”

“What?” Reisner replied.

“I’m on my way to knock off Jack Anderson.”

“W-what?”

“You heard me.”

“Jeb said that?”

“Told me to get rid of him, plain as day.”

“Oh, well I’m sure he didn’t mean that!”

“Yeah? Well, where I come from, kid, that means a rub-out.”

Liddy turned around and left. Behind him he could hear the sound of Reisner running to Magruder’s office. Wanting to see the reaction, Liddy waited by the elevators and let several go by. Reisner barged into Magruder’s office.

“Did you tell Liddy to kill Jack Anderson?” Reisner said with a horrified look.

“What?”

“Liddy just rushed past my desk and said you’d told him to rub out Jack Anderson.”

“My God,” Magruder replied. “Get him back in here.”

Reisner found Liddy by elevators, where he had been waiting for a few minutes, and escorted him back to Magruder’s office.

“Gordon,” Magruder clarified, “I was just using a figure of speech, about getting rid of Anderson.”

“Well, you’d better watch that,” Liddy answered as he feigned frustration in his voice. “When you give me an order like that, I carry it out.”

In Liddy’s account, he never left the elevators and instead dealt with Reisner; he made his exit more dramatic:

“Oh, Gordon, I was afraid you’d be gone. Jeb said he most certainly definitely did not mean it that way. Just forget it. Don’t do anything! He was just kidding!’

Grinning inwardly, I fought to be stern as I said, “Damnit, he better learn how to make up his mind. That stuff’s nothing to kid about.” An elevator arrived and I left.

“I’d never known anyone like him,” Magruder later reflected, “and I was beginning to wish I’d never met him.” Magruder had one more task for Liddy, this time one that could be approved. Liddy and his associates had stolen documents of interest from the Democrats in the Watergate Office Building and Magruder wanted more, particularly to know what dirt the Democrats had on the Republicans. He pointed at a section of his desk where “he kept his derogatory information on the Democrats,” Liddy claimed. “Whenever in the past he had called me in to attempt to verify some rumor about, for example, Jack Anderson, it was from there that he withdrew whatever he already had on the matter.” Anderson in a strange roundabout way would end up ending the Nixon presidency, although he was aware of none of these actions at the time.

Facing the Wannabe Assassin (1980)

Q: Jack, did you ever fear for your life or livelihood during the Watergate era?

ANDERSON: Not exactly. I didn’t find out until later that two of the—two people on the White House payroll were actually thinking of knocking me off. One was G. Gordon Liddy, the other E. Howard Hunt. They discussed it. They actually talked to a CIA doctor about getting some kind of poisons or drugs to use against me. And G. Gordon Liddy has admitted this in his book….But at the time, I didn’t know about it.

Q: Is it true Liddy said to you, when you met him—and we obviously now know the man would have killed you, and threatened to kill you. Is it true he said to you, “Don’t take it personally? Nothing personal”?

ANDERSON: Essentially, that is right. It was a professional matter with him, he said.

Jack Anderson was preparing to sit across from Gordon Liddy in person in 1980 for a TV appearance. Liddy had been released early from his 20-year prison sentence in 1977 for his involvement in the Watergate scandal, ultimately serving four and a half years after his sentence was commuted by President Jimmy Carter. Liddy thought that facing Anderson was akin to a meeting of former combatants, as if they had been in war. Anderson wanted to punch him in the nose, he later revealed, but instead he shook Liddy’s hand. Anderson charged Liddy and his compatriots with inventing their rationale for his assassination: “You can’t name any CIA agent whose death or execution I caused…because it never happened. I don’t reveal the names of CIA agents. I consider that to be reckless.” Anderson continued: “It never happened. You were prepared to kill me because of a wild rumor. Did you ever try to check it out?

“I didn’t say CIA agent,” was Liddy’s response. “I didn’t limit it to that.”

In his separate TV appearance around this time, Hunt lied about the Anderson plot, denying it had involved assassination. He denied even discussing “a need to kill Anderson,” emphasizing that they had only gone as far as exploring an option to discredit Anderson with LSD, dropping the matter, he claimed, when “a retired CIA doctor [Dr. Gunn] said attempts along those lines overseas had been unsuccessful.” Gunn also lied, only admitting in 1975 testimony to discussing the use of hallucinogenic drugs to make a person act “peculiarly.” His retirement, he claimed he told them, precluded him from having access to such drugs anymore. Liddy, for his part, emphasized that Anderson had been a “pain in the butt” to the Nixon White House and that taking him out would have been “justifiable homicide.”

Hunt, who had served 33 months in prison for his role in the Watergate affair, refused to appear alongside Liddy in his TV interview. He later revealed an aspect of Liddy he discovered that disturbed him, that went beyond his willingness to kill on command:

I would only find out about his affinity for Nazi Germany little by little over the course of our relationship. At one point early in our friendship, he asked if he could come over to my home in Potomac, Maryland, to play an important record. I agreed. It turned out to be a German recording of the arrival of Hitler at a massive crowd of supporters. Liddy described the scene as though he were there, his face taking on a rapturous glow.

Later, when our work for the Nixon reelection campaign (which led to Watergate) became more intense...One evening, when the Liddys were dining at our house, Gordon sat down at the Steinway grand piano and belted out a lusty version of a Nazi song, which prompted [Hunt's wife] Dorothy to find something urgent to do in the kitchen.

I was also told on good authority that while Liddy worked for the White House, he arranged a private showing of The Triumph of the Will, the most notorious of the Nazi propaganda films, made by German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl.

Liddy, while not admitting to the events above, revealed his fondness in his youth for Adolf Hitler in his similarly titled memoir Will:

Here was the very antithesis of fear--sheer animal confidence and power of will. He sent an electric current through my body and, as the massive audience thundered its absolute support and determination, the hair on the back of my neck rose and I realized suddenly that I had stopped breathing.

When I spoke of this man to my father, he became angry. Adolf Hitler, he said, was an evil man who would once again set loose upon the world all the destruction of war. It was just a matter of time. I was to stop listening to him.

The lure of forbidden fruit was too strong; I continued to listen, though less frequently...

To change myself from a puny, fearful boy to a strong, fearless man, I would have to face my fears, one by one, and overcome them. From listening to the priests at Sunday Mass, I knew that would take willpower. Even Adolf Hitler agreed. He and his people would triumph through the power of their superior will.

Others in the White House had known Liddy’s predilections as well. Walking one afternoon on a rainy, cold day in March 1972, a White House aide commented to Magruder: “Liddy’s a Hitler, but at least he’s our Hitler.” Magruder noted the insanity of Liddy accessing the upper echelons of power, while admitting: “Perhaps if there had been no Liddy we would have created one.”

Ready to Die (1972)

Shotgun blasts through window of his home on a Sunday morning while his family was at breakfast. Worst of all, the hit man would be a “scared-to-death nonprofessional.” That was how Liddy thought all of this would end.

On a Washington street on June 19, 1972, Gordon Liddy and John Dean were both concerned about their fates. Dean was worried that even being seen Liddy would implicate him further in the criminality and lead to a certain prison sentence (he later served four months). As a mitigation measure, Dean took their conversation outside, with the White House in view behind them.

“This whole goddamn thing is because Magruder pushed me,” Liddy complained. “I didn’t want to go in there. But it was Magruder who kept pushing. He kept insisting we go back in there—”

“Back?” Dean replied, unaware the arrest had followed the second Watergate break-in.

“Yes. We made an entry before and placed a transmitter and photographed some documents. But the transmitter was not producing right...So we went in to find out what was the matter. The other thing is Magruder liked the documents we got from the first entry and wanted more of them...”

Liddy had larger concerns than simply prison time that was looming with prosecution of his crimes on the horizon. A government that would consider using drugs to discredit Daniel Ellsberg or to murder Jack Anderson could certainly turn their attention to eliminating him now that he was persona non grata and the presidency was at stake with the exposure of the Watergate burglaries, Liddy thought. The failure was his responsibility; he was ready to accept the consequences. With visions of his family being murdered while having Sunday breakfast, he decided to offer himself up rather than endanger his family. While walking back up 17th Street, Dean tried to end the conversation as crowds were now gathering. Liddy made the following proclamation: “I want you to know one thing, John. This is my fault. I’m prepared to accept responsibility for it. And if somebody wants to shoot me…” Dean snapped his head around to stare at Liddy, whose face and words were bursting with emotion, “…on a street corner, I’m prepared to have that done. You just let me know when and where, and I’ll be there.”

Dean remembered how Liddy had burned his hand with a candle and contemplated how this situation felt like being in a Mafia film. “Well, ah, Gordon,” he replied. “I don’t think we’re really there!”

“All right. But please remember what I said.”

“Believe me, Gordon, I will.”

Roselli’s Fate (1975-1976)

“Who’d want to kill an old man like me?” asked Roselli after a friend mentioned the possibility that the Mafia would want to do him in for testifying before a U.S. Senate Committee. Behind the scenes, the Mafia was already upset with Roselli over his grand jury testimony in 1971 on organized crime’s involvement in the Los Angeles Frontier Hotel, where he owned a gift shop. That same year, the CIA had been worried that Roselli would reveal his involvement in the Castro assassination plots given deportation proceedings underway against him and intervened on his behalf with the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. After his first appearance before the U.S. Senate on June 24, 1975, Roselli had signed his own death warrant: a Mafia commission decided to take him out. In their view, Roselli had failed to approach them before testifying and “shot his mouth off” without any sense of discretion. “They decided he would just go on talking every time he was pressured and he had to be hit,” a Mafia figure told the press.

Roselli’s killers monitored him off and on for months, waiting for the right moment. “They would watch his movements for a couple of weeks, leave him alone for a few months, then go back and watch him some more. Roselli was careful but nobody can be that careful. When the decision is made to hit you—you’re dead no matter how long it takes.” Two fishermen found a 55-gallon oil drum floating in Dumbfounding Bay and saw human limbs through holes cut in the drum, heavily chained and belonging to Roselli. “Cutting up and disposing of bodies is not necessarily new to our department,” the Dade County homicide squad lieutenant noted macabrely.

Roselli’s death came as a shock to Jack Anderson; he had been one of Anderson’s sources for his articles on the plots to kill Castro. The CIA had done their best to lie about the assassination attempts; in Anderson’s 1971 article “6 Attempts to Kill Castro Laid to CIA,” former CIA Director John McCone “vigorously” denied that “the CIA had ever participated in any plot on Castro’s life.” After his death, Anderson revealed that Roselli’s view was that Kennedy’s assassination had been in retaliation for the attempted hits on Castro:

By Roselli’s cryptic account, Castro learned the identity of the underworld contacts in Havana who had been trying to knock him off. He believed, not altogether without basis, that President Kennedy was behind the plot.

The Cuban leader, as the supreme irony, decided to turn the tables and use the same crowd to arrange Kennedy’s assassination, according to Roselli’s scenario. To save their skins, the plotters lined up Lee Harvey Oswald to pull the trigger.

Fourteen years earlier, Roselli had also informed his lawyer of the same story, told to him by Cuban sources. When asked if he had any facts to back up this assertion, Roselli replied in his U.S. Senate testimony: “No facts.” Anderson noted that his Senate version of tale differed from the one Roselli gave to his close associates. Anderson tried to following up on the leads of Roselli’s theory:

There is no proof, of course. But there is some corroborative, circumstantial evidence. It has been established, for example, that Oswald visited the Cuban consulate in Mexico City two months before the dreadful day in Dallas. An informant named Sylva Duran first stated, then denied, that she had overheard the Cubans speak to Oswald about assassinating someone and had seen them slip him some money.

Several key CIA officials believed that Castro was behind the Kennedy assassination. Two days after the shooting, the CIA cabled from Mexico City that Ambassador Thomas Mann felt the Soviets were too sophisticated to participate in a direct assassination of the President but that the Cubans would have been stupid enough to recruit Oswald.

It has also been established that Jack Ruby indeed had been in Cuba and had connections in the Havana underworld. One CIA cable, dated November 28, 1963, reported that “an American gangster-type named Ruby” had visited Santos Trafficante in his Cuban prison.

Sam Giancana, who was also murdered in 1975 just before he was scheduled to testify before the U.S. Senate, once explained Roselli’s patriotism that led him down his final path: “Just wave a flag and Johnny’ll follow you to any canal.” The day after Roselli’s body was retrieved from the bay, his brother-in-law confided: “Down deep, in a way, I probably hope it was connected with [the Castro affair]. At least then Johnny, he would have died for a cause.”

Fascinating article. Thank you.

Just one fact check: you wrote "In 1960, pressure was mounting from the Kennedy administration to assassinate Fidel Castro."

There was no Kennedy administration yet in 1960. JFK was elected in November 1960 and took office on January 20, 1961.

A small nit to pick, perhaps, but it is sufficiently jarring to interrupt the flow of your otherwise compelling narrative.