“Men ain’t in politics for nothin’. They want to get somethin’ out of it.”

-George Washington Plunkitt, 1905

In his early 20s, Fernand “Freddy” St Germain looked too young to be a state legislator in the Rhode Island House of Representatives. He was elected through an anti-corruption wave that swept fellow Democrats out of office in his hometown riding of Woonsocket. “They were trying to fill the slate and nobody would take the job,” he explained. St Germain accepted the position and in one of his first days in office, his youthful appearance stood out. Standing near the back of the State House chamber in Providence, the House doorkeeper gave St Germain a request, thinking he was a page: “Run down and get me a cup of coffee.” St Germain responded indignantly: “Run down and get your own cup of coffee.” Surprised by the response, the doorkeeper asked: “Whose patronage are you?” St Germain shot back: “Whose patronage are you?” Still bothered by the incident thirty years later, St Germain took from it the following lesson that proved to be prescient: “You give a little man a little power, and he’ll abuse it.”

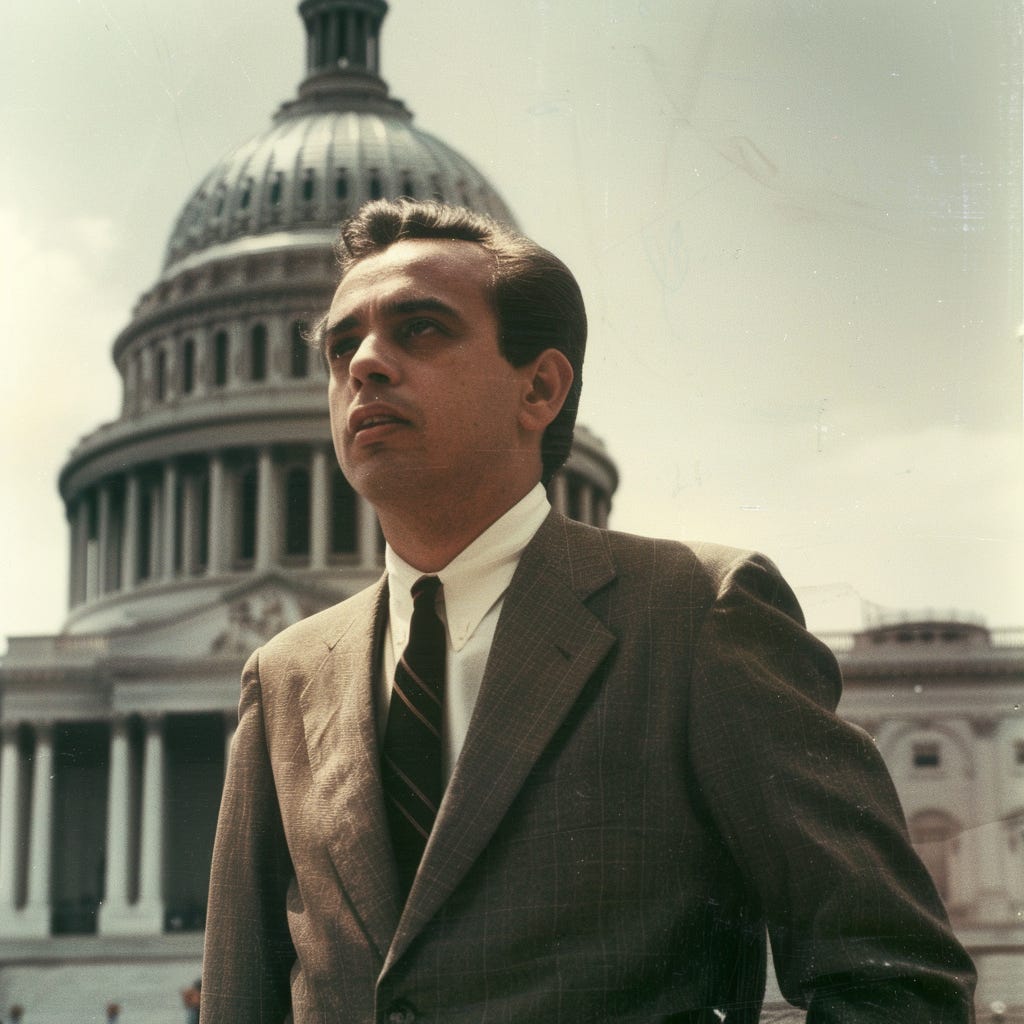

Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1960 buoyed by the momentum of John F. Kennedy on the ticket, St Germain moved his family to Washington, DC but could not find “a home with a yard” that fit within their budget. They settled for renting a five-bedroom apartment in an area largely populated by public servants. St Germain found that congressional salaries left much to be desired. “Whatever you make you’re going to spend,” he said of his salary, which was raised to $30,000 ($300,000 today) annually in 1964. Attorneys and lobbyists made several times the income of the members of Congress they targeted for influence; St Germain was determined to join their ranks and sought out ways to supplement his salary.

In 1971, St Germain approached an old friend, Roland Ferland, a real estate developer, asking to be cut in on future deals: “If something comes along, I hope you’ll consider me.” An opportunity came along in the form of a 192-apartment building in East Providence, Rhode Island. St Germain was the only non-member of Ferland’s family brought into the deal, which amounted to a $3,000 ($23,000 today) investment for a 15% share of the partnership. He cashed in most of his share for $184,798.90 in 1980; all told the deal earned him $192,000 ($550,000 today) by 1986.

Another land deal from Ferland in 1976 located in Pawtucket earned him $176,250 ($500,000 today) in ten years, off an initial investment of $7,500 ($41,000 today). In return, St Germain supported housing subsidies for Rhode Island in the Banking Committee. The real estate developer in turn profited, Ferland becoming one of the largest managers of subsidized housing in the Northeast. A further land deal offered by Ferland, involving a 20% stake for St Germain in School Street Associates purchased in 1975, made St Germain less money, only $18,000 ($52,500 today) in profit when it was sold in 1985. “This finally concludes one of our less profitable partnerships,” Ferland wrote when sending St Germain a check. “I guess we can’t have all winners.” Without noting the conflict of interest, chairman St Germain of a banking subcommittee overseeing financial institutions invited Ferland to testify regarding proposed legislation before the subcommittee in 1978 and again in 1980.

While chairman, St Germain’s most infamous property deal came in 1972. International Industries was looking to dump its International House of Pancakes (IHOP) restaurants at below-market prices and St Germain seized upon the opportunity. Putting up no money of his own, St Germain received loans totaling $1.3 million ($9.8 million today) and he purchased two restaurants in Rhode Island, along with three in Maryland, New York, and Texas. For the Rhode Island restaurants, the federally regulated Industrial National Bank provided the 100% financing, while a state-regulated institution, Marquette Credit Union, refused a similar request until he inflated the selling price to be $15,940 ($120,000 today) higher than the actual amount.

The IHOP investments were not guaranteed to be profitable, with one of the lenders writing the following: “The outlook for continued successful operation is in doubt.” This proved to be true, as St Germain pressured the institutions to provide him with longer mortgage terms to reduce his monthly payments to increase his take-home amounts for the rental payments the properties generated. As expected, International Industries had difficulties making its payments; however, St Germain received $20,000 ($104,000 today) in late penalties from the company in 1977. He earned a profit of $315,995 ($955,000 today) from selling just one of the Rhode Island restaurants on New Year’s Eve in 1984.

St Germain kept his ownership in the properties hidden from the public under an entity called Crepe Trust until 1978, when disclosure rules forced him to list his assets. Regarding the seed money of the trust provided by the Industrial National Bank for the IHOP restaurants, St Germain later claimed to investigators that it “was not his money and that he could not recall where it came from.” When reporting on his Ferland and IHOP properties, he undervalued the real estate. The three Ferland deals were listed at a total value of less than $3,000, whereas he was to earn $390,000 from them in a few short years. In 1983, he valued the IHOP restaurants at $300,000, while he claimed they were worth $1.8 million in a separate loan application.

While taking issue with St Germain’s underreporting of his assets, a later ethics committee investigation found nothing wrong with the investments themselves. For the Ferland deals, it determined that his “participation in those transactions was not the result of any influenced exerted by him on the Ferland Corporation or associated banking interests” and that his “involvement in the Ferland Corporation investments was due primarily, if not exclusively, to his long-standing friendship with Roland Ferland who was the general partner in those undertakings.” With regard to the IHOP investments, the committee thought “St Germain could reasonably be characterized as a willing buyer who accepted the offerings of a more-than-willing seller. In this regard, the Committee adduced no evidence suggesting improper influence exerted by the congressman in obtaining the properties or either the initial mortgages or subsequent recasting of loans on those properties.”

After getting involved in a further real estate deal in 1980 in Florida, St Germain explained the investments after his hidden participation was once again exposed: “It’s like anything else. You sit down with your buddies and say, ‘Do you want in?’ And you either say yea or nay.” While St Germain never saw an issue making these investments while serving as a member of Congress, he nonetheless liked to joke that there was no period in the abbreviation of his last name (“St”) since he was no saint.

PACs

Guy Vander Jagt, appointed as Republican House fundraiser-in-chief in 1975, set out on a mission to encourage businesses to set up political action committees (PACs) to influence the political process. “They were still reluctant as hell,” he recalled of the companies. “I spent a good deal of ’75 and ’76 going around beating them over the head.” PACs had first formed in the 1940s as a vehicle for labor unions to contribute to Democrats. Vander Jagt was determined to turn the tide for Republicans by way of contributions from businesses, that he expected would greatly overtake what labor could muster.

Vander Jagt’s speeches, boosted by his oratory skills and training as a minister, were geared toward his evangelism of corporate takeover. Speaking to Dow Chemical executives in Michigan, he said:

“Into Washington have moved the Ralph Naders, the consumers, the environmentalists, the labor unions, and all of the rest. And they really can’t do anything except impact on political decisions. They don’t have any achievements to their credit. That’s all they do, but boy, they do that very, very well. And they’ve moved into the vacuum that you have left for them because you’ve been doing more important things.”

An opening in the system was created by Neil Staebler, a Democrat appointee on the Federal Election Commission, who was denied reappointment by President Carter given his vote joining with Republicans to allow Sun Oil Co. to establish a PAC. Staebler later reflected on his decision: “I think it would be very bad government, very bad politics, to permit one part of our society to do things forbidden to other parts.” Vander Jagt scolded those business interests dared to ignore the fruits of Staebler’s martyrdom and not exploit the floodgates that had now opened: “This Democrat gave his political life to open the door for you, and if you then don’t have the gumption to walk through that open door, to take advantage of the chance he gave you, you have no right to call yourselves Americans.”

To Vander Jagt’s shock and dismay, once formed, the business PACs gave mostly to incumbents, rather than to Republicans predominately. He had expected them to follow the model of labor PACs; 95% of their money traditionally went to Democrats. “It never even occurred to me that if business formed PACs the great bulk of the money wouldn’t go to Republicans,” Vander Jagt admitted. He went on to brief President Ford and Chief of Staff Dick Cheney that only 4% of business PAC money went to GOP challengers; they were equally dumbstruck. “Ford wouldn’t believe me; he didn’t think it was possible. So I wasn’t the only stupid one.”

Carousel

Tony Coelho was at the end of his rope at the age of 22 in the summer of 1964. Diagnosed with epilepsy, he lost his driver’s license, was unemployed, and watched as his friends worked summer jobs or moved on to new careers. A profound depression began to develop and he would drink each night, looking on as waves from the Pacific Ocean crashed on the beach. Other times he would go to a nearby park and watch children ride on a merry-go-round, the carousel music remaining in his brain for years afterward. He toyed with taking his own life. “Every night I ended up passing out, drunk…I had gone downhill very fast. And I woke up one morning, and I was hung over, I was dirty, couldn’t really recall where I had been. And I started thinking that there wasn’t any hope. What was I going to do? There was no hope whatever for the future. Everywhere I turned there was rejection. And then I started thinking: the best way to resolve this, the easiest way to resolve this, was suicide.”

“You’re killing yourself,” a friend told him. “I know,” Coelho replied. The friend offered him an opportunity to work for comedian Bob Hope in Palm Springs. Coelho was rejuvenated: “All of a sudden life took a different twist.” While in his employ, Hope suggested Coelho work in politics. Through Coelho’s uncle, he got an interview with his local Democratic congressman, B. F. Sisk. Coelho was offered an internship and he drove illegally across the country in 1965 to take the job: “That was the beginning of a whole new life.”

Five years later, Coelho became Sisk’s administrative assistant and on his second day on the job, a lobbyist slipped him an envelope containing five $100 bills (worth $4,000 today) and a business card. He could not tell if the money was meant for him or the congressman, but he knew it was illegal. He worried about it all day: was his boss taking bribes? He knew of other House members who routinely demanded money from lobbyists before speaking to them. Was he now expected by Sisk to be a conduit for illicit payments? “I believed in him and I believed in the system, and I didn’t want to be disappointed,” Coelho recalled.

Coelho brought the $500 to Sisk’s attention. “You’re the AA,” Sisk told him. “What are you going to do with it?” Coelho replied: “I want to send it back.” The congressman treated it as an annoyance not worth his time: “Well, why don’t you?” Sisk answered. “That’s your job, you know. I expect you to handle it.”

Coelho was relieved; he returned the money through a cashier’s check. The lobbyist resented the perceived slight: “He tried to get me fired,” Coelho recalled. Some lobbyists had difficulty understanding the subtleties involved in giving money to politicians, how discussions had to be more indirect than direct: “I’ve got guys coming into my office who are felonies waiting to happen,” Coelho’s future colleague Pete Stark explained. “I’ve got dip-shits talking about tax amendments, and in the same breath talking about raising money. You could put them in jail for that.”

Selling Souls

In 1985, a decade after Vander Jagt’s PAC realization, not much had changed; incumbents continued to be favored by business donations and there appeared to be no end in sight to the Democratic majority in the House. In a June 1985 memo to House GOP members, then congressman Dick Cheney wrote: “I have been, and continue to be, a strong believer in the PAC system. But I do think we Republicans need to remind our friends in the PAC community that we are determined to become the majority party in the House of Representatives, and that we do not look kindly on organizations that help the Democrats perpetuate their majority.”

On the campaign trail, Guy Vander Jagt expressed his frustration that business interests were only giving money to those who had the best chance of influencing legislation in their favor. It was a big money system in which both parties were being bought, without a semblance of ideology or loyalty to be found. He yelled in a moment of frustration: “The PACs are whores!”

Now a member of the U.S. House of Representatives himself, Coelho learned from the House Speaker Tip O’Neill of how contributions previously flowed to members of Congress in the dark without accountability or transparency: “in the old days [O’Neill] would go around the country and play gin at parties. On the bed would be a bag, and people would just throw in thousands, or whatever it was, and at the end of the evening he would just grab the bag and take off, and that’s how he raised his money…And people talk about our system being corrupt. There are members of Congress who used to charge people when they came in the office to lobby. And it would be in cash.”

Hoping to rise to the senior ranks of Democratic House leadership, Coelho took the job of chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, becoming in the process Vander Jagt’s counterpart on the other side of the aisle. With enough distance from his prior problems, Coelho by this point had found “inner peace” and he was willing to do whatever it took to win, which included raising funds for his Democratic House colleagues and helping their campaigns. His sights were set on becoming Majority House Whip, the second-highest ranked position in party leadership. Representative Stark expressed his view on what leading the DCCC meant in moral terms: “You can’t be in that job and not sell part of your soul. There is no way.”

A Horrendous Crime

In June 1980, 17-year-old David Weidert was working as a janitor in the office of Dr. David Edwards, a physician in Fresno, California, when he decided to rob his employer. He happened to run into 20-year-old Michael Morganti that night. The two were already acquainted and Weidert decided to take advantage of Morganti’s mental disability and recruit him to be part of the crime. After discovering the burglary, Dr. Edwards confronted Weidert several times about it, on the last occasion informing him that he knew what happened as Morganti had been an eyewitness. Weidert responded coldly: “Nobody is going to believe that idiot in court․ I’ll see to it that they don’t.”

Five months later, Weidert had just turned 18 and convinced 17-year-old John Arbigast to join him in an effort to kill Morganti to prevent him from testifying in court. The two drove to Morganti’s neighborhood and waited for hours for him to appear. Once he did, Arbigast walked up to his apartment door, using a lure suggested by his girlfriend to trick Morganti into joining them. After Arbigast introduced himself, he told Morganti that his sister wanted to meet him. They went to a parking lot where Weidert was waiting with a knife and Morganti was forced into their truck. After driving for about a mile, they stopped to tie Morganti’s hands behind his back. They drove for 30 minutes and arrived at a mountainous, isolated area northeast of Fresno.

Once the truck was parked, they all got out and Weidert ordered Morganti to start digging, handing him a shovel. He was then instructed to lie in the grave, after which Weidert began hitting Morganti in the head with a baseball bat. Weidert passed the bat to Arbigast, who also hit Morganti. Weidert asked for a knife; Arbigast turned away, but he could hear Morganti scream.

Morganti was now buried in the shallow grave, but as Weidert attempted to walk across it, Morganti’s hand came out of the ground and grabbed onto Weidert’s leg. As his head also became visible, Weidert wrapped a telephone wire around Morganti’s neck and strangled him. Once Morganti stopped struggling, Weidert hit him in the groin with the baseball bat; seeing no reaction, Morganti was reburied in the grave. He was later determined to have died from suffocation.

No official proceedings regarding the burglary at Dr. Edwards’ office had commenced at the time the murder was committed. A prosecutor later testified that Weidert, a minor when he committed the robbery, would have likely received probation without any jail time. Since he had legally become an adult when he committed the murder, he now faced life in prison. Arbigast, a minor, was offered immunity in exchange for his testimony against Weidert.

Back in Washington, DC, Coelho was busy trying to come up with ways to reduce Weidert’s sentence. His father had been a donor to his congressional campaign. Coelho’s assistant tried to warn the congressman against taking this stand: “Tony, it’s a mistake. It’s a political mistake…”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Memory Hole to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.