The Importance of Eye Contact

It was not long after meeting Patrice Lumumba during his trip to Washington, D.C. that the U.S. Government knew he had to die. As the first prime minister of the Republic of Congo elected following Congolese independence in June 1960, Lumumba spent the first few months of his term seeking support to help stave off a Belgian-supported secessionist movement. “Lumumba is an opportunist and not a communist,” wrote the U.S. deputy ambassador, Robinson McIlvaine, in July 1960. “His final decision as to which camp he will eventually belong will not be made by him but rather will be imposed upon him by outside forces.” Stating publicly he would accept support from any source, Lumumba approached the United States in July to be that outside force for the Congo. Instead of meeting with President Dwight Eisenhower, who was on vacation, he spent a frustrating 30 minutes with Secretary of State Christian Herter and his staff. Lumumba requested U.S. assistance with persuading Belgian troops to leave the Congo; Herter referred him to the United Nations. Lumumba requested the use of an American plane; Herter suggested he check with the United Nations for U.S. planes they may have to spare. Lumumba requested an official loan; Herter suggested that any money be channeled through the U.N. as a conduit. The meeting ended without any clear commitments made on the part of the United States.

From their perspective, the State Department representatives believed they were clearly dealing with a lunatic. The U.S. Under Secretary of State C. Douglas Dillon found Lumumba to be an “irrational, almost psychotic personality.” Lumumba demonstrated to them that he was impossible to work with due to “the impression he made rather than the individual things he said,” speaking to them, they noted, in “fluent French” (Lumumba would have had little difficulty speaking fluently, this being the official language of the Congo). Dillon expanded that this view was bolstered by a lack of eye contact: “When he was in the State Department meeting, either with me or with the Secretary in my presence…he would never look you in the eye. He looked up at the sky…And his words didn’t ever have any relation to the particular things that we wanted to discuss…You had a feeling that he was a person that was gripped by this fervor that I can only characterize as messianic. And he was just not a rational being.” Feeling rebuffed by the United States, Lumumba next sought support from the Soviet Union, a classic communist takeover move in the view of the U.S. Government and necessitating his removal from power. Herter wrote to U.S. Ambassador William Burden that Lumumba’s reliability was “open to serious question. Lumumba’s intentions and sympathies unclear, and evidence exists that he will...not prove satisfactory. U.S. will therefore continue search for more trustworthy elements in Congo who might be susceptible to support as part of program of reinsurance against Lumumba.” Dillon concluded that the “willingness of the United States government to work with Lumumba vanished after these meetings...The impression that was left was...very bad, that this was an individual whom it was impossible to deal with. And the feelings of the Government as a result of this sharpened very considerably at that time.”

Shortly after Lumumba’s visit to Washington, Dillon attended a meeting at the Office of the Defense Secretary at the Pentagon where the possibility of “eliminating Lumumba” was raised. The visit had “convinced us that Lumumba was psychopathic, not in a well-balanced mental state. After his visit we wondered whether there was any way of changing the scenery in the Congo.” Ambassadors from the State Department let decision makers know that they “would not shed a tear” if Lumumba were to disappear.

In August, at a meeting of the National Security Council, the center of U.S. covert foreign policy decision making, Eisenhower gave an explicit order to assassinate Lumumba. Robert Johnson, a notetaker at the meeting later told investigators what the President had said while other attendees cited issues with their memory. Johnson explained: “After a review of world events, which included a description of Mr. Lumumba’s activities in Africa, Eisenhower turned to Dulles during the meeting in full hearing of those in attendance, and said something to the effect that Lumumba should be eliminated…there was stunned silence for about 15 seconds and the meeting continued.” The participants, Johnson felt, gave off the impression of being in “great shock”; after all, “it was uncharacteristic of Eisenhower to speak of anything of substance during NSC meetings.”

By September, the NSC meeting minutes reflected the Council’s growing impatience, with CIA Director Allen Dulles remarking that “Lumumba was not yet disposed of and remained a grave danger as long as he was not disposed of.” Dillon explained it was not the possibility of Soviet influence, but rather Lumumba’s character as a person that sealed his fate: “My impression of seeing him was that he certainly wasn’t controlled by them or anyone else, he was so far gone himself that nobody could rely on him as an individual.” To make the situation worse, the U.S. learned that Soviet Premier Khrushchev had sent Lumumba a gift, his own executive aircraft.

Sid from Paris Visits the Congo

On September 19, 1960, Larry Devlin, the CIA’s Chief of Station for the Congo in Leopoldville, received the following cryptic instructions:

HE SHOULD ARRIVE APPROX 27 SEPT . . . WILL ANNOUNCE HIMSELF AS “SID FROM PARIS” . . . IT [IS] URGENT YOU SHOULD SEE HIM SOONEST POSSIBLE AFTER HE PHONES YOU. HE WILL FULLY IDENTIFY HIMSELF AND EXPLAIN HIS ASSIGNMENT TO YOU.

This cable and the subsequent visit, Devlin later recounted with bitterness, would plague him for the rest of his life. A week after receiving the instructions, Devlin was leaving the U.S. Embassy when he recognized his Agency colleague Sidney Gottlieb, Chief of the CIA’s Technical Services Division, sitting at a nearby café. Gottlieb stood up and wordlessly followed Devlin into his car. The two drove away with Gottlieb in the passenger seat. Devlin already knew Gottlieb’s identity since he had helped Devlin with installing listening devices in a previous operation. Gottlieb nevertheless continued with the spy routine: “I’m Sid from Paris,” he said as he turned to Devlin. “I’ve come to give you instructions about a highly sensitive operation.” (Gottlieb’s use of the moniker “from Paris” was interesting in retrospect, since he wound up being sued decades later stemming from an incident in Paris, where he was accused of secretly drugging an American with LSD. Gottlieb denied having been in Paris at the time during his deposition.)

After arriving at Devlin’s personal apartment (which he later erroneously referred to as a CIA safehouse, evidently to imply the location was secure enough to handle the conversation that followed), Gottlieb explained why the assignment’s instructions could not be relayed via cable as per the regular protocol: Devlin was to assassinate Lumumba and Gottlieb had brought deadly poisons to accomplish the task.

“Jesus H. Christ!” Devlin exclaimed. “Isn’t this unusual?”

Gottlieb retrieved from his bag a virus and two other poisonous biological agents developed to kill Lumumba, along with rubber gloves, a gauze mask, and a hypodermic syringe for the purpose of administering the substances. Handing these to Devlin, he explained how the poisons could be injected into food, drinks, toothpaste, or anything else that Lumumba might be expected to ingest. As a junior Chief of Station, Devlin was not accustomed to political assassination being part of his regular duties. Devlin pressed Gottlieb on the source for this order:

Devlin: Where did this brilliant idea come from?

Gottlieb: The top.

Devlin: Who at the top?

Gottlieb: The Director has instructions from President Eisenhower.

Gottlieb continued: “It’s your responsibility to carry out the operation, you alone. The details are up to you, but it’s got to be clean—nothing that can be traced back to the U.S. Government.” Such an operation was not new to Gottlieb, whose labs were later found to have stored “enough exotic poisons to eradicate the population of a small city.” If the killing were to be accomplished without a trace, certainly poisons would show up in a human body through an autopsy, Devlin worried. Gottlieb responded that these lethal agents would leave normal traces as found in individuals who die from known diseases. Asked how long the poisons would remain lethal, Gottlieb replied they would be useful only for a few months. That limits certain possibilities right there, thought Devlin, who was surprised at the short timeframe he had to work with. Fearing that administering the substances would pose a challenge, Devlin suggested that shooting Lumumba could be a viable alternative.

Despite his operational reservations, Devlin later testified before Congress that he told Gottlieb he “would explore this….I stressed the difficulty of trying to carry out such an operation.” Gottlieb for his part was left with the impression that Devlin was “sober [and] grim,” but willing to carry out the order. Devlin claimed to have taken a further step to confirm this unusual assignment: “I responded to Headquarters with a double-talk message, saying that I had met the messenger and [was] requesting confirmation. I then received a cable containing double-talk confirmation, something like, ‘Your assumption confirmed.’” Contrary to the double-talk message he claimed to have sent, the official cable record confirms that Devlin wrote back to headquarters on the 27th that he and Gottlieb were “ON SAME WAVELENGTH…HENCE BELIEVE MOST RAPID ACTION CONSISTENT WITH SECURITY INDICATED.”

In his memoir, Devlin goes to great lengths to explain his disapproval of the idea of assassinating Lumumba; however, despite whatever thoughts were in his mind, this in no way prevented plans from proceeding. Furthermore, Devlin’s cable from the 27th outlined his top choice for assassination, written in coded language: “HAVE HIM TAKE REFUGE WITH BIG BROTHER. WOULD THUS ACT AS INSIDE MAN TO BRUSH UP DETAILS TO RAZOR EDGE.” This referred to the idea of having an agent with access to Lumumba (“big brother”) deliver the poison to him surreptitiously. Within three days, Devlin received authorization from Headquarters to explore options with an agent named Schotroffe “TO ASSESS HIS ATTITUDE TOWARD POSSIBLE ACTIVE AGENT OR CUTOUT ROLE.” Devlin asked this agent with access to Lumumba the extent of that access, “did he have access to the bathroom, did he have access to the kitchen, things of that sort,” without letting him know the purpose of his queries. Gottlieb left the Congo on October 5, but he “left certain items of continuing usefulness” as the team in Leopoldville continued to implement the operation. The Station reported back to Headquarters on October 7 that the agent had “SUGGESTED SOLUTION RECOMMENDED BY [HEADQUARTERS]. ALTHOUGH DID NOT PICK UP BALL, BELIEVE HE [IS] PREPARED TAKE ANY ROLE NECESSARY WITHIN LIMITS [OF] SECURITY [TO] ACCOMPLISH OBJECTIVE.” Devlin later reflected with amazement that he found himself in “a pretty wild scheme professionally.”

In some ways, the CIA’s task of neutralizing Lumumba as a political force had already been accomplished for them. Earlier on September 14, Colonel Mobutu Sese Seko had launched a coup d'état, and as Devlin recalled, “Lumumba had been essentially neutralized within his…home and office complex where he was under guard by the United Nations.” Thanks to these developments, “there was a lessening in my own feeling of urgency,” when it came to the assassination plot.

Complicating Lumumba’s ability to hold onto power was Katanga, a breakaway province for which Lumumba had requested U.S. and U.N. assistance to suppress the secessionists. David Doyle, a CIA officer stationed in Katanga, was tasked with seeking intelligence on its leader, Moïse Tshombe. Doyle attempted to use Tshombe’s personal secretary for this purpose and he asked a potential agent he was trying to recruit to obtain information through having an affair with the secretary to get her to reveal Tshombe’s “real character and plans.” The prospective agent, whom Doyle referred to as a “lusty European,” returned a week later.

“I wasn’t able to go through with it,” he explained.

“Why not? What happened?” Doyle responded.

“Oh, she came out with me every night. We dined and then went to her place for a nightcap.”

“Well?”

“David, I did my best for you. But have you ever tried to stuff a marshmallow into a piggy bank?”

The Assassins: QJWIN/WIROGUE:

“ZRRIFLE is ostensibly a program to recruit criminals for teams which could break into foreign embassies to steal codes. However, there is evidence in the files that this purpose, though useful to the Agency, was in reality a cover for another operation. From other sources, it appears that the real purpose was at least kidnapping and possibly murder.”

-Top Secret Summary on ZRRIFLE/QJWIN

Dissatisfied with Devlin’s lack of progress in assassinating Lumumba, the Agency sent in Justin O’Donnell, an officer several grades senior to Devlin, to complete the work. Headquarters thought Devlin was too distracted: “SEEMS TO US YOUR OTHER COMMITMENTS TOO HEAVY [TO] GIVE NECESSARY CONCENTRATION PROP.” Devlin breathed a sigh of relief for two reasons: 1) it would take the pressure off him to accomplish the task on his own and 2) he was able to remain as Chief of Station, with O’Donnell reporting to him despite their differences in seniority. Knowing O’Donnell to be a hard worker from years before, Devlin was surprised to discover a lackadaisical attitude in the current-day O’Donnell: “I had the impression he was not that happy even to be there.”

Before leaving Washington, D.C., O’Donnell had been briefed by his superiors on the Lumumba assassination plot (“clearly the context of our talk was to kill him”) and a visit to Gottlieb’s office allowed him to learn “that there were four or five…lethal means of disposing of Lumumba…One of the methods was a virus and the others included poison.” Gottlieb made no mention of the fact that he had already visited the Congo and provided the same means to Devlin. O’Donnell expressed concern to Richard Bissell, the CIA’s Deputy Director for Plans, “that conspiracy to commit murder being done in the District of Columbia might be in violation of federal law.” In response, Bissell, “airily dismissed” this possibility. O’Donnell’s idea was to attempt to draw Lumumba away from the U.N. guard to facilitate his capture by Congolese authorities, resulting in a trial and possible execution. Adding to his point, Bissell reminded him that there was always assassination as a fallback option: “Don’t rule it out.”

Soon after his arrival in the Congo, Devlin told O’Donnell about a virus being held in his safe. He assumed it was lethal and meant for Lumumba; “I knew it wasn’t for somebody to get his polio shot up-to-date,” O’Donnell joked. Contradicting Devlin’s account that he opposed the assassination on moral grounds, O’Donnell later testified that Devlin “would not have been opposed in principle to assassination in the interests of national security…I think I would have to say that in our conversations, my memory of those, at no time would he rule it out as being a possibility.”

A speech from Lumumba on a balcony gave the CIA officers another more traditional idea for assassination. Doyle recounted that he and a fellow colleague named Mike were “expert shots with military experience” and hence proposed “that Lumumba could be shot at long range with the proper equipment. We suggested to Larry Devlin that we would, if necessary, be willing to do just that.” Doyle claimed that Devlin “as a devout Catholic” rejected the proposal, but the cable record shows that Devlin made such a request to CIA headquarters for a “HIGH POWERED FOREIGN MAKE RIFLE WITH TELESCOPIC SCOPE AND SILENCER. HUNTING GOOD HERE WHEN LIGHTS RIGHT.” Devlin himself confirmed that “at one point I requested a rifle with a telescopic site, but I don’t recall it ever arriving.”

The CIA’s main issue at the time was a lack of access to Lumumba, who remained under U.N. guard, as a cable on November 14 noted: “CONCENTRIC RINGS OF DEFENSE MAKE ESTABLISHMENT OF OBSERVATION POST IMPOSSIBLE…TARGET HAS DISMISSED MOST OF [HIS] SERVANTS SO ENTRY [THROUGH] THIS MEANS SEEMS REMOTE.” Earlier, Devlin had written to Headquarters that in the view of the U.N., the Congolese arresting Lumumba would be “JUST A TRICK TO ASSASSINATE LUMUMBA,” but the CIA encouraged it nonetheless: “STATION HAS CONSISTENTLY URGED [CONGOLESE] LEADERS ARREST LUMUMBA IN BELIEF LUMUMBA WILL CONTINUE BE THREAT TO STABILITY CONGO UNTIL REMOVED FROM SCENE.” As part of this aspect of the plot, O’Donnell made contact with a U.N. guard in an attempt to recruit him as an agent to lure Lumumba out of the protective custody, stand trial and be executed, since O’Donnell was against assassination on principle but “not opposed to capital punishment.”

The Leopoldville CIA station had two agents already onsite, not believed to be suitable for assassination, and therefore, headquarters proposed a third foreign national be sent to carry out this plot in a cable on September 22: “WE ARE CONSIDERING A THIRD NATIONAL CUTOUT CONTACT CANDIDATE AVAILABLE HERE WHO MIGHT FILL BILL.” This candidate was known as QJWIN, whose real identity was Jose Marie Andre Mankel, a criminal whom the CIA had recruited as an agent in Europe. Emphasizing the importance of the assignment, CIA Director Allen Dulles reiterated two days later that Lumumba had to disappear: “WE WISH TO GIVE EVERY POSSIBLE SUPPORT IN ELIMINATING LUMUMBA FROM ANY POSSIBILITY [OF] RESUMING GOVERNMENTAL POSITION OR IF HE FAILS IN LEOP[OLDVILLE], SETTING HIMSELF IN STANLEYVILLE OR ELSEWHERE.”

It took until November for QJWIN to be sent to the Congo. O’Donnell wanted him to work as his “alter ego,” someone he knew from experience was “dependable, quick-witted,” and capable of any action, including murder. By late November, Lumumba had left U.N. custody to travel to Stanleyville, which did not deter QJWIN, with a cable noting that he was anxious to go there by himself to carry out the plan without any assistance required. That plan, the CIA Chief of Africa Division confirmed, could include assassination, only if the United States’ hands could be kept clean: “WE ARE PREPARED [TO] CONSIDER DIRECT ACTION BY QJ/WIN BUT WOULD LIKE YOUR READING ON SECURITY FACTORS. HOW CLOSE WOULD THIS PLACE [UNITED STATES] TO THE ACTION?”

Separately, Devlin sought further outside help from another agent under the cryptonym WIROGUE/1, whose tasks were enumerated as “(1) organizing and conducting surveillance team (2) interception of pouches (3) blowing up bridges and/or (4) executing other assignments requiring positive action.” WIROGUE/1 was described as someone who “learns quickly and carries out any assignment without regard for danger.” The agent was “aware of the precepts of right and wrong, but if he is given an assignment which may be morally wrong in the eyes of the world, but necessary because his case officer ordered him to carry it out, then it is right, and he will dutifully undertake appropriate action for its execution without pangs of conscience. In a word, he can rationalize all actions.” A long study found in the CIA’s files on WIROGUE/1 , whose real name was David Tzitzichvili, likened his lack of morality to being “like a man who wants to kill an elephant—all he wants from us is a high-powered rifle—then he feels he would be equal to the elephant.” Tzitzichvili, who had lived for years in France, was “stateless” soldier of fortune according to his file, who possessed a criminal record as a forger and bank robber. A dispatch from the Chief of Africa Division revealed the lengths taken to conceal his identity: “WIROGUE/1 underwent plastic surgery, which changed the shape of his nose...A toupee had been made for his constant use. This and the plastic surgery have altered him sufficiently to obviate any recognition.” He was trained “in demolitions, small arms, and medical immunization,” the latter being particularly useful when it came to the idea of delivering Gottlieb’s lethal biological agents.

A memo from the CIA in Leopoldville revealed the Station’s early enthusiasm with their latest agent’s arrival: “WIROGUE ONE APPEARS [TO] BE JUST WHAT [THE] DOCTOR ORDERED.” However, WIROGUE/1 soon lived up to his pseudonym and began causing problems, attempting to outsource the assassination operation even further by recruiting QJWIN, without realizing that the latter was also an agent of the CIA. A December 17 telegram from the CIA Station outlined how WIROGUE/1 had offered to QJWIN “three hundred dollars per month to participate in intel net and be member ‘execution squad.’” QJWIN turned him down, likely because he had already secured employment in the assassination field. This lack of judgment caused the Station to have doubts and they described how Devlin was “CONCERNED BY WI/ROGUE FREE WHEELING AND LACK[ING] SECURITY. STATION HAS ENOUGH HEADACHES WITHOUT WORRYING ABOUT [AN] AGENT WHO [IS] NOT ABLE [TO] HANDLE FINANCES AND WHO [IS] NOT WILLING [TO] FOLLOW INSTRUCTIONS. IF [HEADQUARTERS] DESIRES, [WE ARE] WILLING [TO] KEEP HIM ON PROBATION, BUT IF [HE] CONTINUE[S TO] HAVE DIFFICULTIES, [WE] BELIEVE WI/ROGUE RECALL [IS THE] BEST SOLUTION.”

In his termination paperwork the following year in September 1961, the CIA noted: “WIROGUE/1 did manage to establish himself in a position of potential value and therein implement the objectives of the project.” Through his termination, he earned a total of $5,150 ($51,530 today) from the Agency.

This use of agents, while of dubious value at the time, later formed the basis of a future permanent on-demand assassination program developed by the Agency, known internally under the euphemism Executive Action: “The White House urged Richard Bissell to create an Executive Action capability; i.e., a general stand-by capability to carry out assassinations,” wrote the CIA’s Inspector General in 1973. “The Executive Action program came to be known as ZRRIFLE. Its principal asset was an agent, QJWIN, who had been recruited earlier…for use in a special operation in the Congo (the assassination of Patrice Lumumba). to be run by Justin O’Donnell.”

As part of a memo to pay QJWIN on January 11, 1961, he was noted as having been “sent on this trip for a specific, highly sensitive operational purpose which has been completed.” A specific objective had been achieved by late 1960: Lumumba was now in the hands of Congolese authorities.

The Death of Lumumba

A CIA cable on November 14, 1960 revealed the extent to which the Agency was monitoring Lumumba’s attempt to escape his U.N. guardians: “DECISION ON BREAKOUT WILL PROBABLY BE MADE SHORTLY. STATION EXPECTS TO BE ADVISED BY [AGENT] OF DECISION WHEN [WILL BE] MADE…STATION HAS SEVERAL POSSIBLE ASSETS TO USE IN EVENT OF BREAKOUT AND STUDYING SEVERAL PLANS OF ACTION.” After Lumumba had escaped, Devlin held discussions with “Congolese officers to the effect that they were trying to figure out how to head him off.” He recalled “there were only a certain number of ferries and river crossings…there were a limited number of roads, and he had to go through deep rain forests and major rivers were crossed.” On November 28 the CIA cabled: “[STATION] WORKING WITH [CONGOLESE GOVERNMENT] TO GET ROADS BLOCKED AND TROOPS ALTERTED [TO BLOCK] POSSIBLE ESCAPE ROUTE.”

Continuing on into January 1961, the CIA was kept informed of Lumumba’s condition and movements, but the cable trail in terms of CIA direct orders and involvement at this point ran cold. After Lumumba’s recapture and detention by Congolese authorities, Devlin felt that it was over: “Once we learned he had been sent to Katanga…his goose was cooked, because Tshombe hated him and looked on him as a danger and a rival.” While Devlin claimed he was “not a major assistance” in tracking and capturing Lumumba and that efforts to assassinate Lumumba had stalled during the previous year, a financial record showed otherwise, as noted by author Susan Williams:

“In his memoir, Devlin stated that on 13 January 1961, Mobutu, Nendaka, Kasavubu and several others in the Binza group went to Thysville. But he himself, he insisted, had no idea what was going on. He heard ‘many rumors’ about the Thysville mutiny and the subsequent removal of Lumumba, but he did not get involved. Devlin was lying. A newly released document reveals that he sent WIROGUE to Thysville in January.”

Frank Carlucci, future U.S. Secretary of Defense, then working for the U.S. Embassy, was witness to a captured Lumumba being transported from Leopoldville to Binza: “As it was,” he recalled, “I was probably—I and then Senator Gale McGee—were probably the last two westerners to see him alive. We were having a drink about mid-afternoon at a sidewalk café and a truck went by. Lumumba had his hands tied behind his back and was in the rear part of the truck.”

Lumumba final destination was Elisabethville, where he arrived by plane on January 17th. Lumumba was beaten so severely on the flight, the pilot warned that the violence and commotion was threatening the safety of their flight. David Doyle was stationed at his post in Katanga, upset by the “international hue and cry” of Lumumba’s arrival. “I was so frustrated by the intrusion of his presence into an already complicated, delicate and at times frenetic situation, in which I had insufficient assets to cover events, that I cabled Leopoldville: ‘THANKS FOR PATRICE. HAD WE KNOWN HE WAS COMING WE’D HAVE BAKED A SNAKE.’ A copy went to headquarters, and the communicator feared that I would be fired as a result. However, Ed Welles, then chief of the Africa Division branch that handled the Congo, sent me a cartoon of two Texas baking a snake—the first sign that I wasn’t going to be fired. I learned later that the cable had appealed to CIA Director Allen Dulles’s sense of humor, which certainly saved my skin.”

Within five hours of his flight’s landing in Elisabethville, Lumumba was murdered along with two political associates, Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, by a firing squad featuring officials from Katanga and Belgian police officers in the jungle on January 17, 1961 at approximately 9:43 pm, according to a Belgian investigation. On the same day, President Eisenhower delivered his Farewell Address to the Nation: “In the councils of government,” he said, “we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military–industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists, and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals so that security and liberty may prosper together.” Susan Williams noted the tragedy that Lumumba and other African leaders “weren’t opposed to the U.S. They wanted friendly relations with the U.S. but, because they weren’t opposed to the Soviets either, they were seen as enemies by Washington. The attitude was ‘you’re either with us or against us.’”

After Lumumba’s death, Devlin went into his safe at the CIA Station to retrieve the virus and poisons Gottlieb had given him and bury them near the Congo River. “I think that I took them out probably in a briefcase or an air bag of some sort,” he remembered, “and I believe that the things like the rubber gloves and the mask were thrown away in a bushy area or something where, you know, if they were found it didn’t matter that much.” Devlin testified before the U.S. Senate Church Committee in 1975, where Gottlieb also revealed that he had destroyed records related to tests on poisons developed to kill Lumumba. “I am aware that some people believe I should have rejected the order to implement the operation,” Devlin later wrote in 2007, “but I do not regret the way I handled it.”

Gerard Soete, a Belgian member of the police force in Katanga, recalled being tasked with making the bodies of Lumumba and his two associates disappear. Right before Lumumba’s assassination, the executioners offered Lumumba the opportunity to say his final prayers. Lumumba responded by refusing and laughing at them, Soete’s superior officer recalled. Similar to the U.S. officials before them, the Belgians believed they were clearly dealing with a lunatic. Soete and his associates returned to the scene of the crime the next morning and “saw a hand coming out of the ground, one of the dead.” He outlined the gruesome process that followed:

“We cut the bodies to pieces. Well, they were buried twice, but then we cut them into pieces, we burned them, we also had a huge amount of acid…like in car batteries. And in that most of the bodies were immersed. The rest we burned. But it had to be done without the blacks seeing it, in the heart of the forest. That was a problem too. There were two of us and we had to do all that ourselves, to remove the three bodies from the earth, cutting them into pieces, destroying them. And all of that could not be revealed to anyone and no one knew about it.”

Soete kept some of Lumumba’s teeth as a memento and proudly displayed two front teeth for a documentary film crew. He laughed that while there was talk of repatriating Lumumba’s body to the Congo, the transfer could never be complete with the missing two front teeth. After Soete’s death, his daughter showed another gold tooth to author Ludo De Witte, claiming that it belonged to Lumumba. In 2022, the tooth was returned to the Democratic Republic of Congo and buried as the only known remains of Patrice Lumumba.

A Belgian investigation in 2005 found no conclusive evidence linking the CIA to Lumumba’s death. In the 2022 edition of the The Assassination of Lumumba, Ludo De Witte concludes that the CIA played no role in the death of Lumumba, relying on official statements and CIA cables. One account that was excluded from this history involves a 1965 lecture at the Farm, the CIA’s covert training facility near Williamsburg, Virginia. A case officer was explaining the peculiarities of what life in the CIA could mean for the new recruits in attendance, as part of a lecture describing what he had experienced in Katanga province as a case officer. For him in 1961, his job had entailed “driving around town in [Elisabethville] with Lumumba’s body in the trunk of my car,” trying to decide what to do with it. At the time, the multiple burials of Lumumba’s body in different locations was not known to the general public. John Stockwell was one of the junior CIA officers listening to the speech, taking notes. “He presented this story in a benign light, as though he had been trying to help,” Stockwell explained. “He was a CIA case officer among the mob of people over there. He may not have even had a title at that time.” The extent of CIA involvement beyond this anecdote remains unanswered and it retained special significance for Stockwell, as he later became the CIA’s Chief of Base in Katanga. He never asked the officer about it: “I didn’t have a chance...he finished his lecture and left.” Stockwell would encounter this officer two further times in his career, including in Asia and Europe, but to this day his identity has not been revealed. While he refused to name the man on principle, Stockwell confirmed that while he worked in Katanga “men I had worked with had been involved” in Lumumba’s assassination. Stockwell happened to run into Devlin before his Church Committee testimony in 1975. “Certainly he would never perjure himself,” Stockwell wrote of Devlin’s proposed approach, “his testimony would be consistent with any written record and provable facts. At the same time I guessed that only he and President Mobutu would ever know the complete complete truth of Patrice Lumumba’s assassination.”

U.S. attitudes towards the Congo persisted in the ensuing decades. Daniel Simpson, the U.S. Ambassador to Zaire (formerly the Congo), in a 1996 speech contrasted current perspectives with those of the 1950s: “That was probably what people said in 1958 and 1959, when the Congo was coming to independence: ‘Oh, they can’t do that…Congolese are not capable of governing themselves. This country can’t do that.’” Devlin happened to be listening in the audience and the Ambassador caught his expression of dismay. “Larry Devlin is shaking his head,” Simpson remarked, “I know that he knows that’s true.”

Tai Chi: 1975

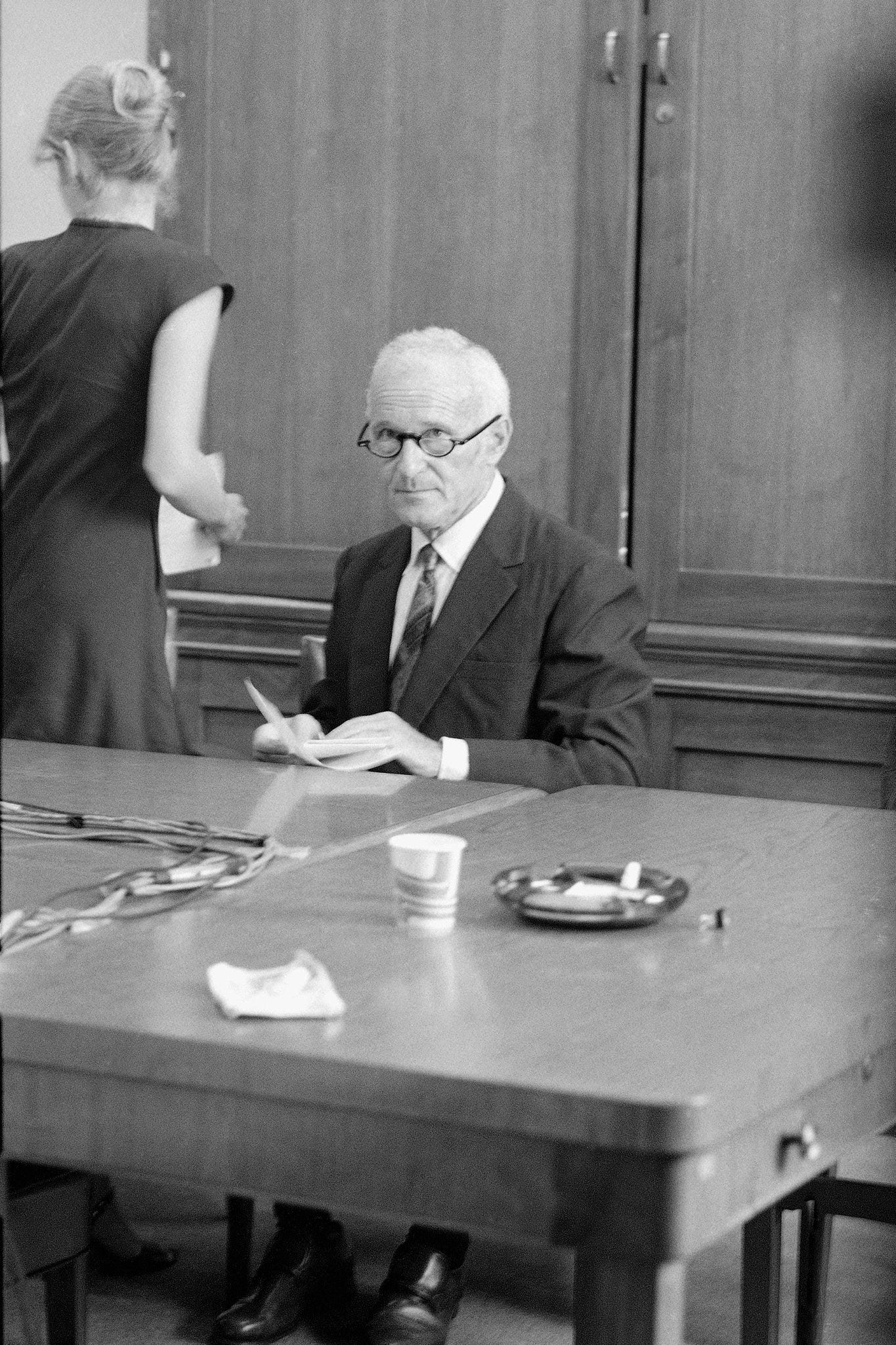

Alone with his lawyer in a small room during a break from his Senate testimony, Sidney Gottlieb was having a panic attack. His face drained of color, breathing heavily, he closed his eyes and began moving his arms in slow, measured motions that looked to his lawyer, Terry Lenzner, like Gottlieb was dancing.

What on earth is this? Lenzner thought.

“Tai chi,” Gottlieb explained without being prompted. “Helps me relax.”

“Sid,” his lawyer pleaded. “Help me out here. What’s in that memo?”

“That’s the one,” Gottlieb confided. “The one that worked.”

Part 2 to follow.