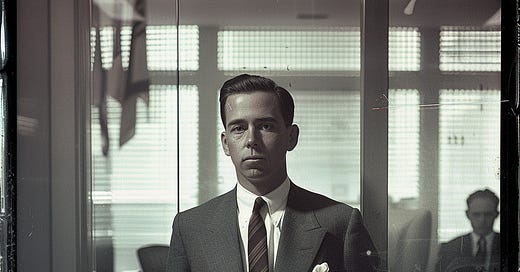

“Win Scott was, when I knew him, how shall I put it, a demigod: a navy captain, an FBI man with a Ph.D. in mathematics, one of the pillars of the original communications intelligence effort, very handsome, very much of a womanizer. We thought this was a real hero…I didn’t know anybody more important.”

-Thomas Polgar, CIA Officer from 1947-1981

James Angleton, counterintelligence chief of the CIA, rushed into Mexico in April 1971 to visit the recently widowed wife of a former CIA station chief. His primary mission was not to offer condolences, but rather to hide Agency secrets. Winston Scott had recently died at the age of 62, two years after retiring as CIA Chief of Station in Mexico City, a position he had held from 1956 to 1969. He had let it be known to Agency officials that he was working on a memoir of his life entitled It Came to Little. The title reflected his views on the limited progress that had been made in covert operations over his decades of experience in the OSS, FBI, and the CIA. Editor John Barron at Reader’s Digest had convinced him to re-title it as The Foul Foe. Reader’s Digest Press had expressed interest in publishing the book, with the caveat that it would need to be reviewed by the CIA for redactions: “The book was not in publishable form,” Barron recalled, “and I had told Scott we would have to have clearance from the CIA.”

Angleton explained the severity of the situation to Scott’s third wife Janet with regard her late husband’s memoir: “The information in there would, if it was made public, violate two different secrecy agreements that he signed,” Angleton claimed. “Damn it, Janet, this is important. It would do great harm, grave harm, to our relationships with other governments, with some of our closest allies. Win wouldn’t want that. It would disturb his friends.” Angleton’s request was simple: hand over the manuscript and anything else related to the CIA among his effects.

Janet was convinced to not read the memoir, as Angleton claimed part of the draft contained intimate details of his previous marriage. She immediately agreed to cooperate and handed over all copies of the unfinished memoir. As it turned out, there was a lot more to transport back to Agency headquarters. A CIA officer went through the voluminous classified material Scott had stashed away. The CIA took everything they could find, including surveillance audio of the Black Panther Party: “We have found [the] Huey Newton and [Eldridge] Cleaver tapes, but these [are the] only tapes so far,” the Mexico City station wrote to HQ. In one safe, they found a locked box. “We suspect this may contain missing tapes on [journalist John] Rettie case and ‘lesbians.’” The CIA later found tapes marked Oswald and photos of Oswald from his trip to Mexico before the Kennedy assassination and the Agency was particularly concerned with keeping their existence and Scott’s thoughts on these items hidden from the public.

Informants for the FBI

Born in Alabama in 1909, early on his career Scott realized his dream of being a Special Agent of the FBI. Despite his multiple degrees in mathematics, he convinced his boss, Assistant Director Hugh Clegg, whom the agents called “Trout-Mouth” due to his unusual facial features, to not assign him to the cryptography division of the Bureau. Instead he was permitted to go out into the field and he was soon transferred to the Pittsburgh Field Office.

Most field or “brick” agents were assigned on a rotating basis to the Complaints Desk. A Special Agent would sit in an office near the entrance of the FBI building and a receptionist would pass on walk-ins that entered to see them. It was the early period of World War II and many Americans wanted to help the war effort by reporting information they thought the FBI should know. Scott found out that there were hundreds of Americans actively working of their own accord, attempting to assist the FBI by seeking out what they believed to be important secrets. While many had good intentions, there were many were “just plain and simple nuts,” in Scott’s view. One of these included a man named Sam Searles whose mouth was permanently kept agape. Searles claimed that if his upper and lower natural teeth touched, they acted “as a receiving station for messages from Berlin.” This radio frequency in his mouth required him to keep his mouth propped open at night for him to be able to sleep. Despite Searles’ teeth being filled with cavities, he refused to have them replaced by a dentist to non-receptive fake teeth; the supposed intelligence information he received through them was too important.

On a daily basis, Searles would arrive at the Pittsburgh FBI Office with carefully typed pages to be left with a Special Agent on the desk; only after he confirmed with the receptionist that the Agent could be trusted. “This man, and others like him, who came into the Office,” Scott explained, “no matter how absurd the story, had to be treated with courtesy and thanked for the help they thought they gave to the United States of America.”

Some informants would stop making their visits to the FBI once they figured out that actions were not being taken in response to their questionable intelligence reports. Some simply wanted their neighbors to be arrested and would keep an eye on the street outside their home for the moment when an FBI raid would befall their nemesis. When that moment never came, some of the informants would become anti-FBI in their views, since the Bureau was not taking their concerns seriously. Searles, however, for his part never stopped informing the FBI regarding what his teeth told him: “Some resourceful Special had convinced him that the messages he brought to the FBI were so secret,” Scott recounted, “when deciphered, that a very few people could be told what they said, what they contained when in clear text.” After World War II had ended, the frequency of Searles’ teeth was adjusted to pick up secret messages from Moscow and he continued his pursuit of being an informant to the FBI in Pittsburgh. His teeth were never extracted; “he went with cavities to his grave, as a patriot—a nut, but a very patriotic one!”

Churchill

While on assignment with the FBI in Cuba following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Scott felt he was not contributing enough to the American war effort and sought a leave of absence to join the Navy. Shortly after being assigned to a naval radar research laboratory, he met a former FBI colleague who convinced him to join the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which would later become known as the CIA. He spent time at the OSS’ training farm in Virginia, where he was given firearms training, as well as being taught how to fight an enemy in close quarters and how to kill silently. The five weeks of intensive physical and mental training in the world of espionage Scott believed was “even more concentrated than the weeks in the FBI Training School at Quantico.”

Scott was assigned to the X-2 Counter Espionage Branch of the OSS in London, where he participated in planning deception operations with MI5, the British Security Service. Prior to his arrival, their biggest success had come with an operation in 1943 in which a body had been taken from a London morgue, food pumped into its stomach and left adrift off the coast of Spain from a British submarine. The corpse was given a fake identity, military paperwork, and was attached to a briefcase in which forged documents were stored to pretend that an invasion of Greece and Sardinia were imminent, to misdirect the Germans from the true invasion of Sicily that was planned. Scott learned this had been “one of the most successful deception operations of the war.” He was keen to contribute to the operations through MI5’s Twenty Committee (its name stemming from XX in Roman numerals, representing “double cross”), which he believed “played a major role in winning the war against the Nazis.”

Scott helped MI5 draft a plan that he thought had the potential to be a great deception operation. He was invited by his U.K. counterpart, intelligence officer Tommy Robertson, who was dressed in a Scottish Black Watch Colonel’s uniform, to present the plan to Winston Churchill. The Prime Minister had stipulated that all such operations were to be clearly through him personally and the pair traveled to 10 Downing Street to make the pitch. The two officers had difficulty retaining their composure as they walked past guards in the halls of the Prime Minister’s residence; Scott himself felt “more shaky” than his companion.

The Prime Minister grunted a welcome as the two entered Churchill’s private office. Robertson made a brief pitch outlining the deception plan, handing Churchill a piece of paper on which the proposed operation had been concisely captured. Churchill took great care to read the document slowly. He is reading this with great interest, Scott thought. Robertson was relieved they were not being subjected to an intense line of questioning regarding their proposal. Churchill picked up a pen on his desk and drew a diagonal line across the page and wrote something in the bottom right-hand corner. He handed them back the paper and they were summarily dismissed. Scott did not understand what had happened until he caught a glimpse of the page: at the bottom, Churchill had written the word “Balls.”

Their “dream plan” dashed, the pair left 10 Downing Street and went to the nearest pub, contemplating how best to describe the failure to the team that had spent the bulk of the time on the plan. They decided a brief, factual recitation of the events would be preferable. Robertson gave Scott the piece of paper, which he kept “as one of my treasures, a piece of loot gathered during World War II.”

Purple Heart

In August 1944, following the Battle of Cherbourg, Scott accompanied the U.S. Navy on a patrol torpedo boat to retrieve one of the few OSS agents behind enemy lines in Germany. On the journey, they were pursued by German E-boats and a Colonel in the U.S. Army named Sam Rosenberg became seasick and went below deck to recover. He soon fell out of his bunk and broke his arm. This injury earned Rosenberg the Purple Heart, a military medal awarded to those wounded or killed in the line of duty. Unbeknownst to Scott at the time, he would soon be awarded the medal under even more outrageous circumstances.

Back in London, the city had sustained tremendous damage during the Battle of Britain in 1940 and was now, in the later phase of the war, under continued attack from Nazi Germany in the form of V-1 flying bombs and V-2 rockets. Scott described their attributes in his memoir: “The V-1, with its putt-putt which when it cut off meant that it was beginning the descent and one should run for cover when it was near; the V-2, which hit first and one heard the sound later, if he were alive; both these were like the dying gasps of a monster which had struck its mightiest blows already and had now begun to thrash about in its death agonies.”

After receiving his whisky ration from the U.S. Navy, Scott and his friend John Houghran went out pub crawling one night in London, landing in the Grapes, “a pub noted for its noise and for its tarts.” They found “a very pretty girl, obviously a tart” who wore a hat over half of her face, reminiscent of Veronica Lake, a popular American film actress of that era. Houghran prompted Scott to sit next to the woman and Scott asked her back to their apartment for a drink of Scotch whisky. She readily agreed and the three returned to the mews flat nearby. As the woman, named Ona, took a seat to share a drink with them, she removed her coat and hat, revealing a huge scar across her face that had disfigured one eye; a war wound, she told them. Scott was devastated: “She was suddenly horrible looking!” he recalled.

“Old Man, you first!” Houghran suggested to Scott. Both Houghran and Ona were insistent, however. Ona in particular was looking to earn five pounds sterling, her fee for each of them. Scott took her back to his small room and they began undressing, Scott studiously avoiding looking at her face. In the moments before turning off the light, he looked at her straight in the eye, the scar running across the rim of her eyelids and her completely white blind eye were seared into his mind as the light was turned off. Scott was pleasantly surprised as “she let herself go, as if she were grateful for this chance to release the tensions which must have been pent up inside her. I soon felt like I was riding atop a high and mighty wave. She was wonderful!”

Relaxing afterwards, the two remained in bed and Scott fell asleep, awakened by the sound of a V-1 flying bomb overhead, the noise stopping as it reached their building. Already the victim of a previous bombing, Ona grabbed Scott in fear. They had sex a second time as the bomb hit the apartment.

“Did you ever make love while flying?” Ona asked.

“No, but I believe we will both have had the experience of making love while dying!” Scott replied.

The building was shaken by the explosion but they continued as if nothing dangerous was occurring. A small water tank attached to Scott’s bathroom was nudged from its perch high up on the wall and landed directly on his head. A flash like lightning appeared in his mind and then everything went black as he was knocked unconscious. Ona screamed, pushing what she believed to be a dead body off of her. She immediately got dressed and ran out of the building.

“Hello Dare! Old Man!” Houghran’s voice sounded in Scott’s brain as he regained consciousness. Standing over him, Houghran informed Scott that Ona had left, not wanting to be part of the investigation of his presumed death. After getting dressed, Scott was visited by a U.S. Navy lieutenant who tried in vain to have him go to the hospital. An official accompanying the lieutenant took copious notes and Scott’s war injury was deemed as warranting a Purple Heart medal. Scott believed this to be the only time the military decoration had been awarded for being slightly injured while being serviced by a prostitute.

Philby

When Kim Philby, the British intelligence officer, got very drunk, a “state of inebriation he reached quite frequently,” he described to Scott how he would go to a small Russian restaurant in Soho meet with his Soviet friends. It took several years before Philby and his associates, known as the Cambridge Five, would be revealed as secret Soviet spies.

One of the Cambridge Five was Guy Burgess, who was also no stranger to alcohol. Throughout his career, he would be fired for being drunk at work and be caught drunk driving while enjoying the privileges of diplomatic immunity in the United States. At Martin’s Tavern in Washington, DC, while Burgess was working at the U.K. Embassy, Scott witnessed his drunken behavior firsthand. Burgess stumbled into the restaurant, covered in vomit and dirt from falling into a nearby ditch. The waiters desperately tried to keep him out of the establishment, but he recognized Scott’s friend and staggered over to them, leaning over their table. “Please help me,” he blubbered, spilling spittle and vomit. “I have no money and I must get home and have a wash!” Scott gave him a $5 bill, after which Burgess exited. A waiter cleaned up the mess Burgess left their table and Scott noted with bitterness that the loan was never repaid.

His secret work spying for the Soviets was to garner significant impacts, even as a low-level employee in the intelligence ranks. According to Scott, while working on the Yugoslav Desk for the British Secret Intelligence Service known as MI6, Burgess rewrote captured German messages to portray Draža Mihailović, a Yugoslav Serb general, as an ally of the Nazis. Scott claimed this led to the shifting of British support from Mihailović to Josip Broz Tito, leader of the Yugoslav Partisans. To Scott, this represented the flaw in intelligence agencies not checking their subordinates’ work. “If anyone had asked to see these messages from the source, and not from Burgess’ files, Burgess would have been uncovered as a Soviet spy in MI6 at the time,” Scott wrote. “But no one bothered—for, after all, Burgess was a Cambridge graduate, one of the ‘Old Boy’ class in England, whom ‘no right thinking Englishman’ could question!”

Scott was a notetaker in the effort to learn from the British intelligence service in establishing the American version, which evolved from the OSS into the CIA. “We repeatedly looked for methods and means by which another Pearl Harbor could be prevented,” Scott explained. “We wanted to assure that intelligence about such a possible event…would get to the officials who needed to know it and not be buried like the excellent intelligence concerning the forthcoming attack on Pearl Harbor was buried.”

Sometimes the errors went in the other direction. Unbeknownst to the British Ambassador in Turkey, Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, secret documents from his safe were surreptitiously leaked to Nazi Germany. His valet, code-named Cicero, photographed the papers, which included plans for the D-Day landing operations. While the Nazis learned a great many secrets, they acted on little of them. Scott read the documents in question after the fact and concluded: “Had the Germans used the information obtained through Cicero intelligently, and had not Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop not believed this operation to be a clever and diabolical trick of the British Secret Service, this unbelievable lack of security on the part of Sir Hughe could have had an adverse effect on the War.” The Germans refused to believed “that such stupidity could exist in a British Diplomatic Installation” and “failed, as they did on so many occasions during World War II, to take advantage of absolutely authentic information which could have helped them and damaged the Allies.”

Stay-Behind Networks

“Puh, puh-puh-puh…” Philby was unable to get his words out. Scott was later convinced that Philby used his pronounced stutter to hide his duplicity. Both he and meeting attendees would feel self-conscious as Philby appeared unable to speak for minutes at a time. “I believe he hid behind this defect, pronounced though it was, many, many times,” Scott claimed, “in order to prevent his colleagues in MI6 and the Americans with whom he had to deal, from knowing how embarrassed he was at the topic under discussion; and to give himself time to settle down and calm his nerves over the possible breach in his cover as a Soviet agent!”

Philby once remarked to Scott on the futility of lie detectors, expressing the belief that “we know who can and who cannot be trusted, simply by looking at his background and by knowing who his friends were in university.” This was telling in retrospect, as other classmates of Philby from Cambridge had joined him in the Soviet spy ring. The Soviet operation not only netted details on U.S. spy personnel, it also allowed the Russians to disrupt ongoing operations.

Following World War II, the U.S. feared that the Soviet Union would extend its sphere of influence beyond its new colonies of Czechoslovakia and East Germany into new territories such as Scandinavia, France, and Italy. In response to this perceived threat, Scott described in partially redacted portions of his memoir how the U.S. buried “weapons, food, communications equipment and systems and cold cash. These items were buried in the ground at marked sites; and it was intended that, when the Soviets over-ran the country or caused communists to take over the government, previously recruited and trusted agents, likely to be able to stay in place, would be given the sites and would have supplies needed for survival and for communications with a base outside that country. The recruits were to be from cripples, very old people, and others who…would likely stay on and be free to some extent—at least free enough to dig up the supplies and report to a wireless operations (likely through a cut-out) who could send the information to a base outside the Soviet area.”

With a Soviet agent now in charge of Section V of MI6, the operation was blown. Philby, Scott suspected, had certainly reported all of the prospective agents to his Soviet handler, rendering the planning useless. Scott revealed that “even if we had succeeded in establishing networks in all the countries we dealt with, they would still have been rolled up; and, it means that, with Kim Philby occupying the position he then held, the problems solved, money and time spent and despite the dedication shown by many, ‘It All Came to Little.’…Philby was able to report on many persons and on details of the stay-behind network project for each of the countries involved. Washington, as usual, sent far too many people to each and every meeting—and thus added to Philby’s reporting and to the ‘blown’ clandestine intelligence officers working for the USA.”

With all of the radio sets, cipher pads for cryptography, and other material buried under ground that the Soviets were able to retrieve, Scott speculated that they “got far richer from the cash they dug up and got better and more fully equipped…than they had ever been before. Whatever happened, the items…disappeared, and very little was recovered and acknowledged by officials who had been involved in these buryings.”

After World War II, Scott was awarded the Bronze Star and returned to Washington as Chief of Western Europe in the clandestine services of the recently reorganized CIA. Scott was given a brief overview of his division and was called by General Walter Bedell Smith, the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) at the time, to brief him on “what I saw as problems and what I planned to do about them.” Scott participated in the merger of two clandestine groups, the Office of Special Operations (OSO) and the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), led by Frank Wisner. Scott called Wisner a “brilliant” man, but one “who talked in long and scrambled sentences when discussing operations of a clandestine nature.”

Scott felt that DCI Smith’s largest strategic error was insisting on maintaining the staff complements of both groups. As Chief of the merger between OSO and OPC, Scott had to listen as both contingents feuded and traded barbs, which often ended in turnover. Scott “had cables from some stations saying, ‘If (that OPC officer) stays in this country, please accept my resignation’; and some two very similar ones from OPC officers saying, ‘If (that OSO officer) stays here, please accept my resignation as of the receipt of this message.’…the combination of these two groups caused a setback for many months and made many people unhappy and caused a few regrettable resignations.” Scott found the mandate of the clandestine services to be too broad; he hoped that the scope of operations would be reduced to procure only “intelligence by clandestine means (which could not be got by overt means) and the jobs of counter-intelligence and counter-espionage,” however “counter-subversion and black propaganda” were added to the list of their responsibilities.

Scott was reacquainted with Kim Philby, who was the British Secret Service’s liaison in Washington dealing with the FBI and CIA, as well as the drunkard Guy Burgess, both still spying for the Soviets. Scott recalled attending a party at Philby’s home, at which Burgess also lived. During the event, Burgess became drunk in short order and Aileen, Philby’s second wife, attempted to convince Burgess to retire to his bedroom. He disappeared momentarily and returned to the party, sitting in a corner of the large living room, a pad of white paper and pencils in his hands. A skilled cartoonist, he began drawing the people he saw as he looked across the room. He settled on the wife of CIA officer Bill Harvey, who “happened to be sitting on the floor with her legs spread apart; and Burgess drew in her most sensitive parts, covered with hair and made the face in his drawing plainly identifiable as Mrs. Harvey.”

By the time Scott got a chance to see the drawing being passed around the room, Bill Harvey had already snapped into action. A “large and strong man, of some two hundred forty pounds,” Harvey grabbed Burgess and knocked him to the floor, got on top of him and placed his hands around Burgess’ neck. Burgess began to turn purple from the lack of oxygen, as Scott and Philby jumped on Harvey to remove his grip, which took considerable effort on their part. Burgess finally went to his bedroom for night and rested, as Scott observed “for he was within a few minutes of death.”

Once Burgess, Philby and others were revealed as Soviet spies, Scott regretted the role he played in saving Burgess’ life. He was only consoled by the fact that Burgess’ death may have led to Philby becoming Chief of MI6 and that Harvey could have been tried and convicted for murder. Harvey enacted his revenge on Philby by drafting a letter for DCI Smith to Stewart Menzies, Chief of MI6, severing Philby’s ties to the CIA. Scott had to take solace in the fact that in exile, Philby, “who always hated the cold, has to live in Moscow under the dire and cruel conditions this implies.” While most of the Cambridge Five had escaped to the Soviet Union by the mid-1960s, Scott was ultimately pleased to have saved Burgess’ life years earlier to allow him to die a natural death in 1963, which for the Soviet spy meant “a drunken death, soaked in vodka and filth.”

Cuckolds

While in his final assignment as CIA Station Chief in Mexico City, Scott watched as the KGB built up their operations against the U.S. nearby. Given its close proximity to the country and lackluster controls at the U.S.-Mexico border, Mexico City was an optimal location from which the KGB could run agents into the United States. Latin American passports were easy to come by and U.S. targets could be accessed by acting as visitors from Mexico without the need for the KGB (political/economic intelligence) or GRU (military intelligence) to establish a home base within the United States.

One case in particular in Scott’s memoir involving a naval captain under the pseudonym Boris Prokovich exemplified the GRU’s “lack of our sense of morals,” in Scott’s view. As Chief of the GRU, Prokovich was under constant surveillance by the CIA given that his role involved seeking secret information on U.S. military installations and missile capabilities. With a wide range of surveillance measures in place on the GRU, the CIA was able to learn that a lieutenant commander, Yuri Masevich, working under Prokovich would leave their common office during the workday to his superior’s apartment, where he and Prokovich’s wife were carrying out an affair. As the apartment was easily to surveil, the CIA would listen as the two had sex (“From conversations and gruntings and other noises…we knew exactly what was taking place,” Scott wrote) and watch as Masevich returned to the office with Prokovich seemingly unaware of the liaison occurring right under his nose.

Looking to cause dissension in the Soviet ranks, the CIA station sought and received approval from Agency headquarters to send a Russian-speaking officer to notify the GRU Chief of this impropriety. Walking to the office one morning, Prokovich was intercepted by the CIA officer who told him that his subordinate was having an affair with his wife. In case this was not clear enough, the officer handed Prokovich a piece of paper outlining the facts as obtained by the CIA using surveillance. Seemingly unperturbed, Prokovich listened to the officer, took the piece of paper without a trace of emotion and continued his brisk walk to the Soviet Embassy. They would need to try again.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Memory Hole to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.