Robert Fierer, a lawyer representing two accused Czech spies, in early 1985 was invited to a Department of Justice building in Washington, DC. On the sixth floor, under the careful watch of a security guard, he was able to examine the evidence the U.S. government had collected against his clients. In addition to documents were FBI recordings made over several years at their workplaces, in their car, and at their home. One day, Fierer’s colleague Steven Westby was leaving the secure area after having listened to one of the tapes, looking as if he had just bitten into a piece of rotten fruit. “What happened, Steve?” Fierer inquired as he walked in. “You have to hear this,” Westby replied.

Fierer put on headphones to listen to the recording that had so disturbed his co-worker. He heard the sounds of his clients, the Koechers, moving about their apartment, and then two more people, who happened to be relatives of Fierer, entered the residence. He sat in quiet horror as he realized what his wife’s brother and his sister-in-law were doing with the Koechers: “what I heard, after a while, were the sounds of sex between them,” he recalled. “My relatives were the Koechers’ partners in swinging! My God!”

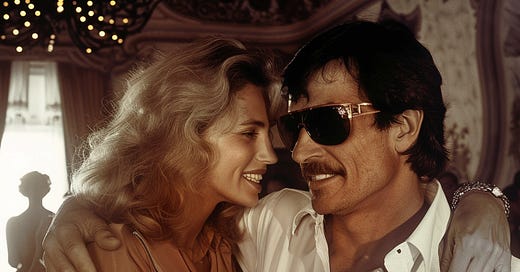

There were other swinging partners involved, Fierer later learned, including a U.S. Army major. This official had been seduced by the wife of the spy couple, Hana Koecher. Fierer began to suspect she played an active role in the Koecher espionage activities. He had no reason to doubt her ability to be successful in these endeavors. “She was beautiful,” he remarked. “She could seduce anyone she pointed at.”

Infiltrating the CIA

Karl Koecher (alternatively spelled Karel Köcher in his country of origin) was familiar with the polygraph by the time the CIA put him through a lie detector test in 1972. He had first encountered one seven years earlier at the Ministry of the Interior in Czechoslovakia. In order to become a spy, he had been trained to deceive the test by a psychiatrist named Milan Dufek. “He had a lamp polygraph there,” Koecher recalled, “it would have been an excellent scene for representing Mephistopheles’ lair.” Dufek’s method involved the test subject visualizing something pleasant when asked difficult questions such as “Do you work for foreign intelligence?” Concentrating on this distraction was key. “Don’t think about women,” Koecher remembered being told, “because it will throw off your reaction.”

The CIA polygraph machine appeared to much more sophisticated than the one on which Koecher had practiced; he immediately noticed there were “no more lamps and wires.” He turned his focus to the teachings of Dr. Dufek: no matter what he was asked, he thought of something pleasant. He also had an easy time with the question: “Have you come into contact with foreign intelligence?” He could truthfully answer that he had reported to the FBI regarding his handler of Czechoslovakia’s secret police, known as the StB. He had also included this fact on his CIA admission form; he only failed to inform the StB that he was making this move. In every step he took, Koecher was careful to weigh all opportunities and above all sought to guard his own interest in every interaction. On the one hand, reporting the existence of his own StB supervisor to the FBI, pretending that his handler was trying to only recruit him rather than assign him agreed-upon work, could be seen as a brilliant move to secure a place in the CIA. On the other hand, the information could later make him appear as an honest actor seeking to aid the United States government, and therefore it also gave Koecher a means of shedding the StB if better opportunities from the enemy side arose.

Since he had recently become a U.S. citizen, Koecher saw great things for himself in the future. If he made it into the CIA, he thought, he could influence the course of world events, including in his home country, which was then in turmoil following the Soviet invasion of 1968. He only needed to get through the next step and pass the lie detector test. To his great benefit, the technician read him the complete list of questions at the beginning before the test had begun. Despite the element of surprise now being removed, Koecher claimed it was his own brilliance that got him through the deception effort: “It’s not that difficult to pass a polygraph. The important thing is that the person who analyzes the data afterwards is not as smart as you.”

Koecher had several skills and a background that were attractive to the CIA: he could translate text from Russian to English, he had recently graduated with a Ph.D. from Columbia University, and had the backing of academics such as George Kline of Bryn Mawr College and Columbia professor Zbigniew Brzeziński, who later became National Security Advisor under President Jimmy Carter. He was also firmly anti-communist, or at least pretended to be in his adopted country, the United States. Now in his late thirties, in a fit of anger at a party he once brandished a bottle in the face of a younger man who happened to espouse left-wing views. “Karel took the bottle and it looked like he was going to break it on him. It was disgusting,” recalled Rolande Pecková, an acquaintance who lived in New York. “Karel talked about the Communists all the time like an obsession. He kept repeating with anger and contempt how much he hated them.”

The CIA employee at Koecher’s initial job interview had told him to expect that the Agency would decline to hire him. Failure in the job process was what most applicants were to expect, he was assured to keep his expectations low. Despite his StB mission, Koecher began to wonder if finding a job at his former university would be better for him personally in comparison with joining the CIA. His former professor Loren Graham did little to encourage him to join the Agency: “I advised him against accepting a position in the CIA, saying that for an American academic such employment could be a fateful step. Even if he later decided to leave the CIA and enter the academic world again he might have trouble finding a good position," Graham recounted. “I told him that many American academics were critical of the CIA and might suspect that he had not severed all ties with it.” In retrospect, Graham found the conversation to have been “ludicrous”: “Koecher must have been inwardly laughing at this moment, since the CIA was the whole reason he had been sent to America…I am sure he filed an intelligence report on my conversation with him.”

After months of waiting, Koecher was invited to a meeting with Milos Vukasin, head of AESCREEN in the CIA’s USSR/Eastern Europe Division. AESCREEN was a cryptonym for the group charged with translating and analyzing materials gathered from the Soviet Bloc, largely sourced illegally through wiretaps. Sitting at a Holiday Inn near Georgetown’s university district, Vukasin explained to Koecher that he had performed well in the translation tests given to him, that he possessed excellent credentials, and that his security clearance process had not generated any red flags. Vukasin could not explain much about the job given the unsecured environment, but as to the details, “You will get to know them as you go,” he assured Koecher. “Karl, we’re taking you.”

A few days later, Koecher was on his way to Langley. His Volkswagen Beetle sped down Virginia State Route 123 until he reached an unmarked turnoff. A guard at the gate verified that his name was on the list and he encountered a series of concrete buildings that were then largely unfamiliar to the public at large. Koecher was surprised to find himself at CIA headquarters. So here I am, he thought. I won’t be coming back. This could be the final location he visited as a free man, if his true purpose for being there were somehow discovered. He looked around for sophisticated security measures, but he could not find many. The last person he saw who was armed inside the building gave him an ID badge that allowed Koecher to pass through the turnstile on the way to the Agency’s main offices. Koecher walked into a large room, in which he saw a giant CIA emblem on the floor featuring the head of an eagle, where a woman was waiting for him. She guided him through a series of gray corridors, leading him to his final set of Agency tests.

Watching CIA employees pass him in the hallways, Koecher marveled at how these were the individuals planning coups across the globe and how they did not look anything like the attractive movie star spies on the silver screen. Are these the people who are protecting American superiority? At first glance, they don’t look like it, Koecher thought. He was first examined by a psychologist, then given an IQ test, as well as a range of exams to test his personality and knowledge of geography and politics. The next day, Koecher was brought in again to meet with a CIA psychiatrist. The only question he remembered from the final test was regarding how he handled arguments with his wife at home; if he remained silent or argued back in these situations. “We are arguing,” Koecher replied. The psychiatrist smiled: “That’s the right answer.”

Rage

Koecher would have lived a quiet, secret double life in the United States if he were capable of keeping his explosive temper under control. Once driving in New York City, he flew into a rage after being stopped behind a car stationed next to the sidewalk. “Why isn’t that idiot driving?” Koecher demanded. His friend alongside of him in the car tried to calm him down. “Don’t be silly, Karl,” the friend said and then explained the reason for their lack of movement. “That car has been parked here for who knows how long!”

The CIA likely missed the elements of his personality that made up later psychological assessments, including determinations such as: “Internally restless, explosive, impatient,” factors that were deemed to be bordering on the pathological. This behavior was also witnessed by his StB handler, who was once subjected to a “rhetorical tirade of insults and obscenities” after he criticized Koecher for not appearing at a previously scheduled meeting. Koecher flew off the handle, accusing the spy handler of siphoning off funds intended for the Koechers that could have helped them to build their life in the United States. “I’d rather deal directly with the Soviets,” Koecher snarled, “who know how to deal with people differently.”

While he was a physically fit individual, to remain in that state Koecher was a terror working out at a local gym. Seeing that a window was once left open by a narrow crack, “He went berserk. He yelled, he screamed, he threatened,” reported an observer. Koecher later picked up a barbell and dropped it on the foot of someone who, in his view, was taking too long lifting weights. “He was in very good shape,” a gym trainer said, “but he was weird.” While Koecher’s rage made him stand out in a crowd, it also made him less likely to be suspected as a spy, given his complete inability to keep his emotions in check when dealing with personal matters. Why would a person act like this if they were also intending to spy on the CIA? In an act that bolstered his unintended cover, within weeks of joining the Agency he was already complaining to his superiors that the work was beneath him in the form of a memo that read: “My present position is by no means one that would require a Ph.D. I am interested in intelligence work, and I want to stay with the agency and do a good piece of work. But I also think that it would be only fair to let me do it in a position intellectually far more demanding than the one I have now...”

Nightwatchman

When 19-year-old Hana Pardamcova first met Karl in the summer of 1963 at a warehouse party, he worked there as a nightwatchman. He had previously worked as a teacher and had to leave his job for a disturbing reason, but she did not know any of this at the time. Hana was ten years younger than Karl, who was immediately drawn to her. He spent most of the night staring into her gray-blue eyes and speaking with her incessantly, feeling as if he had known her for a long time. Even when his then-girlfriend, Milica, entered the room, he attention on Hana never wavered. Fed up with being ignored, after some time Milicia approached Koecher and, without saying a word, she slapped him across the face with her palm. Leaving in tears, his now former girlfriend “knew a lot more than I did at that point,” Koecher conceded.

Within a month, Koecher asked Hana to marry him. He included in his pitch the stunning revelations that he was working with the StB, had the codename of Pedro, and was expected to travel overseas for his espionage work. Two months later, on November 22, John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, CIA officer Nestor Sanchez passed a hypodermic syringe of poison to an agent in Paris with the intent of killing Fidel Castro, and Karl and Hana were wed at the Old Town Hall in Prague, all on the same day. A week before, the StB had committed to paper Koecher’s secret mission: “We agree to the preparation of the prospective dispatch of agent Pedro to the USA...We see the goal of the dispatch in his long-term stay in the USA, where he would settle and create a new home there and the prerequisites for infiltrating an object of our interest.”

Prague Intel

“You are so beautiful!” Václav Havel, author and future Czech leader, was kneeling in front of Hana Koecher, praising her physical appearance at a New York party in 1968. This reaction, while not always expressed so openly, was not uncommon. Meeting with Hana in a Wienerwald restaurant in New York, StB officer Richard Zítek recorded details about Hana that were of questionable intelligence value, including a description of her wardrobe: “a red velvet jacket, a green three-quarter length skirt up to mid-thighs, high-heeled shoes, a yellow blouse with a red scarf and jewelry.” He added to his report: “She kissed me goodbye.” Zítek’s colleague Emanuel Havlík found that their frequency of contact was “quite high” and he soon took over the handling of her case personally.

After receiving his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1971, Karl Koecher had begun teaching at Wagner College, a private liberal arts institution located on Staten Island. The college, he admitted to his former professor Loren Graham, was not “distinguished enough” to warrant his time, but “it would do for now.” Koecher invited Graham to have dinner at his apartment in Manhattan, located at 300 West 55th Street. Graham found the couple to be living “remarkably well” despite Koecher’s meager income. Koecher explained that they lived comfortably in their well-furnished abode because Hana worked “in the diamond trade.” Although it did not completely explain their sources of income, Hana had worked her way up from a lab assistant to a diamond grader for luxury jewelry companies and occasionally worked as a freelance translator for books and articles. Early on in her career, an engagement ring for one of President Lyndon Johnson’s daughters was purchased at Harry Winston, Inc. in New York, where Hana worked in the sorting room. It is possible that LBJ’s daughter ended up wearing a ring at her wedding handled by a foreign intelligence agent.

Incredibly, the StB nearly never found out about their highest placed asset inside U.S. intelligence. Koecher had broken off contact with the StB for two years during his time in the United States, then re-engaged his handlers and lied to them, claiming that he had begun working for the Pentagon as a specialist in Soviet and Eastern Europe affairs on a two-year-contract. He explained he was analyzing important files related to Moscow’s Politburo as part of his work. Koecher offered to help the Czech secret police: “Prepare your ideas,” he was recorded as saying on tape, “what could be done from here.” Even though it was not the CIA, the StB was nonetheless impressed with this apparent placement: “Our service has never had an agent in such a position in the U.S.,” an StB officer wrote.

In keeping with his tendency to play both sides, Koecher then informed his supervisor at the CIA that he had been approached by the StB. He had done the same three years prior, informing the FBI that an StB officer had tried to “recruit” him, when in fact, he had been working for the StB all along, albeit half-heartedly. Vukasin, his boss at the CIA, did not seem upset at all by the StB “approach.” Inside CIA headquarters in Langley, Koecher entered an office with an East German flag hanging on the wall and a “No Smoking” sign apparently taken from a Soviet elevator. An FBI agent joined Koecher and Vukasin in the discussion, repeating that this kind of attempted recruitment from the secret police with someone like Koecher was not unusual.

Koecher considered revealing all at this point: he could tell them that he was in fact a secret agent, but he could now work exclusively for the United States. He weighed carefully the risks involved, including that he could end up inside a prison cell for the rest of his life were he to now tell the truth, having fooled the most important intelligence organization in the United States. “I found myself in a labyrinth,” he recalled. Another aspect that weighed on his mind was that the Americans, from what he could tell, did not care about his home country of Czechoslovakia. Of the 13 staff members in AESCREEN, 11 were devoted to the Soviet Union and only 2 were focused on all other socialist countries. Czechoslovakia was “out of the game,” it appeared to Koecher.

While the CIA appeared to be satisfied with Koecher’s loyalty, the StB had their doubts and took a year to reconnect with him again, still having no idea that he worked for the Agency. On August 19, 1974, after landing in Zurich, Switzerland, a lieutenant colonel of the StB walked up to him in the airport lounge: “Karl, I’m glad to see you again,” the man greeted him, pointing out that Koecher’s mother was already there waiting for him. “Do we have a deal or not?”

The next day, at a French restaurant, the StB officer described how impressed the KGB was with his work. After an hour of conversation, Koecher finally revealed that he actually worked for the CIA and that his job involved translating wiretaps, mostly from Soviet and Czechoslovak embassies. To cover up his previous lies, he claimed that this was a recent development, that he had stopped working for the Pentagon and joined the CIA that past September. He disclosed the name of his CIA supervisor, Vukasin, as well as those of his other Agency colleagues. He explained how the CIA was actively wiretapping the office and apartment of Alexander Nikiforov, the head of the KGB in Beirut, as well as surveilling the activities of the Soviet embassy in Bogotá, Colombia and actively recruiting a diplomat there. Not knowing the diplomat’s name, Koecher attempted to describe him: “About 26-30 years old, over 180 cm tall, former CIA pilot from Vietnam.” Koecher highlighted how the wiretaps from the Soviet embassies that he heard were generally useless: “the workers of the USSR are very disciplined,” he explained. In contrast, the employees of the Czechoslovak embassy in Accra, Ghana “talked a lot,” were “indiscriminate in their expressions, to the point of profanity.”

Koecher dropped another bombshell lie the following day on his StB handlers: he had actually quit the CIA before leaving for his European trip. He had been “dissatisfied with his work,” he revealed; given his educational background, translating wiretaps did not bring him the social prestige he believed he deserved. “Couldn’t the resignation be taken back?” the handler pleaded. Koecher countered that he could perhaps stay on until February and fulfill the terms of his original contract, but he would prefer to be a professor at a university. In reality, he had looked for such employment from New York University and Sarah Lawrence College, for instance, but he was rejected by both. Hana’s employer in the diamond business, Savion, offered him half of the $14,000 annual salary he was earning at the CIA. “I was just playing for time and thinking: I’ll see what happens,” Koecher admitted. Now that the KGB was interested in his work, this had increased his interest to stay in the spy game: “Yes, I wanted to make a name for myself in Moscow,” he explained.

Bringing secret documents out of the CIA was a relatively simple task. Koecher was never searched leaving the office as that “would have offended the workers,” according to him. He made copies of the documents at a local library as almost no one possessed a personal photocopier in those days. One day while at work, Koecher was handed a mysterious list at Langley of Czech names by another employee, who asked him to underline the first and last names. Koecher finished the basic task and on his way back to the employee saw that the copy machine was not in use: “I took an article from the newspaper that I wanted to copy, which I did very often, I put it under it and I actually copied the article from the newspaper and in doing so, the letter. And I immediately returned it to him.” Although the StB was intrigued with the list, they cautioned Koecher that he should not risk exposure by bringing secret documents such as this out of the office. If he could remember the contents instead, that would be a better method, they counseled. “It wasn’t a problem,” Koecher boasted. “I have a good short-term memory. Unless many hours had passed, I was able to memorize the text almost verbatim.” Koecher failed to listen to their advice in later taking out a reel-to-reel tape of a phone call of a colonel named Beránek in the embassy in Ghana, a recording which Koecher had been asked to translate. The KGB later deemed this act to be a “fundamental mistake,” as the removal of this material caused “disproportionate risk.”

Hana agreed to act as an intermediary for Karl and began sharing information herself with the StB. Officer Zitek came up to her one day outside of a Wienerwald restaurant on 5th Avenue in New York City: “Didn’t we see each other on the plane to Europe in August?” he asked. “Yes, it was a 747 jumbo jet,” she replied. “I remember you sitting by the window,” the officer responded. Hana mentioned that her husband had interesting information to offer, particularly regarding CIA eavesdropping on the Soviet embassy in Afghanistan. This information was later brought to the KGB’s attention. Three days later, Hana brought further material concealed in a pack of gum. She slid it across the table to Zitek. “Hide it,” she whispered, “there are secrets.” Zitek mumbled his disdainful reply: “Hana, don’t ever do that again, it’s too risky to carry things like this with you.” The pack of gum was later opened, revealing thin sheets of paper, marked Secret, folded between pieces of gum outlining the CIA’s instructions for wiretapping Soviet citizens, which Koecher had copied during a lunch break. This program, codenamed AEPHOENIX, was intended to seek basic data about the attitudes, regulations, and practical life of Soviet citizens abroad. The CIA would then analyze this information, describing what factors made Soviet citizens tend towards alcoholism, sexual indiscretion, or criticism of their own Communist Party and government. Zitek brought this information to a KGB representative, who stated they “would be happy to help arrange meetings” with the Koechers going forward.

At the next Wienerwald meet-up, Hana did not follow her given instructions and again brought a pack of chewing gum containing secrets. This time it was a document from CIA Deputy Director for Administration John Blake explaining how the Agency’s secret phone calls were encrypted, using randomized short-wave and long-wave connections. A new pattern was established and inserted into a computer every day to prevent eavesdropping. If someone tried to listen in, “the speech became gibberish such that no one could understand it,” Koecher said of the method. As with the previous secrets, these were not the most closely guarded in the Agency, but the intel organizations in Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union were nonetheless pleased. Zitek was still upset with Hana’s violation of protocol. The next time, if she tried to pass any documents to him out in the open, he would refuse to take them. “I see, I broke the rules,” she retorted. Zitek could not help but smile as Hana’s beauty made him nervous. According to the cover “legend” established for their contact, Hana was a “close friend” of his. Much to his delight, this meant he could sometimes place his hand on her shoulder. He wondered whether he should kiss her, to help reinforce the legend. He ultimately thought better of it and controlled himself: that would be going too far, he reasoned.

Hana added one secret using the proper oral method of communication: the CIA was spying on the Czechoslovak embassy in Ankara, Turkey. Koecher could stay at the CIA until his contract ended in February, Hana explained, and perhaps if he mentioned he was looking to start a family, he could get a better position outside of AESCREEN. “Our Soviet friends greatly appreciate everything that Karel has achieved so far,” Zitek told Hana quietly. The KGB, however, wanted more: specific information on people Koecher came into contact at the CIA, especially those with ties to the Soviet Union. Details such as names, license plate numbers, and any other biographical data were important. Hana promised to relay this request. Zitek closed with a financial offering: “If Karel wants to leave the CIA because of money, tell him that he doesn’t have to worry about this at all. We will take proper care of you.” Zitek moved a magazine across the table towards Hana. She could see money sticking out of the pages. “That’s five thousand,” he whispered. “For you. But hide it.”

Hana brought the cash home and excitedly laid out the 50 hundred-dollar bills ($32,000 today) across the living room, leading into the bedroom where she waited for Koecher’s return. When he arrived, Koecher chastised her for playing games with fake money. She cajoled him to take a closer look. Once he realized the money was real, they brought out wine to celebrate. Koecher already knew how he wanted to spend it: “Next year, when we go to Germany, we’ll buy a new BMW there.”

Christmas Party

The AESCREEN Christmas Party in 1974 was held at a hotel in Arlington. Other branches of the CIA were in attendance as well, and there was one employee happily snapping pictures of the event. No one thought anything of Koecher taking photographs of numerous people at the party. He offered to develop the photos at a copy center in New York and he kept an extra copy for himself. This time, outside Wienerwald, Hana did not say a word as she passed an envelope to an StB officer containing photos of 78 CIA employees with their names written on the back. Also included were instructions on how the Agency conducted secret communications with defectors from totalitarian regimes in U.S. embassies abroad, as well as information on how the CIA was funding a publication of Jiří Pelikán, the former head of Czechoslovak Television. The StB already knew this last point, having sent a package to Pelikán 13 days previously that exploded upon arrival. He escaped injury and the CIA was later publicly alleged to have funded his magazine Listy, among others across the globe.

A fervent anti-communist in American circles, in front of the Czechoslovak secret police Koecher took a different approach: “he and his wife clearly see today’s crisis situation in the capitalist world,” StB lieutenant colonel Vaclav Králík wrote. On the 30th anniversary of the liberation of Czechoslovakia, the StB was prepared to give Koecher a state award, Králík told him. Koecher was recorded as demonstrating “indescribable joy.” In his report, Králík then walked this back, apologizing for “tactical” confusion given that no official medal had actually been proposed. “I think it wouldn’t be a problem to give him something later,” Králík wrote. After promising a non-existent award, Králík emphasized to Koecher the most important point regarding his work: “Karl, headquarters and our Soviet friends who are enthusiastic about your work are asking you to keep your place in the CIA. It’s an absolute priority.” The StB bugged the Koecher’s apartment while on vacation in Vienna. “No result,” an officer recorded. “They didn’t talk about collaboration stuff at all.”

A Second CIA Contract

When Koecher’s employment contract with the CIA was about to expire, the Agency briefly considered stationing him overseas as part of the Soviet Union/Eastern Europe Branch, where he would be employed in operational work, rather than the analytical kind he had seen at headquarters. In the end, they opted against this, as there was no unanimous opinion in their ranks as to his bona fides. To keep Koecher’s interest, his supervisor Vukasin asked him to help with a program that prepared candidates for employment at the CIA. In a small studio, Koecher was videotaped about his past, hobbies, preferences, and what he liked and disliked about the United States. Afterwards, Koecher was subjected to an array of psychological tests. Using the footage, candidates were then asked to guess his psychological characteristics based on the answers he gave in the video interview.

Koecher learned that he would no longer have full-time work at the CIA in the summer of 1975; he was to be reassigned to the Agency’s Political Research Office under a part-time arrangement. Given his ego, he was assured that the work was prestigious and important, worthy of his great intellect. Impressed with the materials Koecher continued to provide abroad, KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov authorized a payment of $20,000 ($117,350 today) to Koecher. The KGB took a more active role in his espionage work, arranging for dead drop boxes or hiding places where Koecher could give them information directly. Through Koecher’s leaked secrets, the KGB was able to learn how the CIA had exposed Soviet spies in Tunisia, that the CIA knew about the Soviets’ planned invasion of Afghanistan, and that the Agency in Sweden had set up a press agency to release disinformation about the Middle East. Although he was the only known Soviet-linked agent to have infiltrated the CIA, Koecher himself was still not satisfied with his role. He wrote a letter directly to KGB Chairman Andropov that current intelligence methods were “pointless, that we have to know the mindset of the adversary, and not steal some documents from drawers,” he recalled having included in the message. Once the Koechers received the $20,000, they deposited thousands in a Swiss bank account set up by Hana’s sister living in Zurich.

At the Koechers’ New York City apartment, home to celebrities such as Anne Bancroft, Mel Brooks, and Robert Redford, Karl would show his friends a button on his living-room wall. It was an alarm, he claimed, that if pressed would immediately inform the CIA that someone was tampering with his classified documents and officers would immediately rush to his apartment. While some believed his outlandish claims, others were disturbed by his behavior which they came to discover, a friend noting: “He was, on the one hand, extremely smart, a physics professor type. For example, my husband was fascinated by his intelligence. But there was something strange, dark about him…I’m not a prude or a moralist, but the way he spent his free time scared me.” Koecher became involved sex parties that included the participation of CIA employees, acts that were hidden from both the Agency and the KGB.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Memory Hole to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.